THE KINTYRE

ANTIQUARIAN and

NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY

MAGAZINE

Issue Number 34

November 1993

CONTENTS

- Editorial

- A Maker of Illicit Stills; Dr. I A Glenn

- the Wm. Low Supermarket; Angus Martin

- Carradale Rental, 1924

- The Englishing of Gaelic Personal Names; A I B Stewart

- A Wedding at Kilchousland; Angus Martin

- Genealogical Queries

- By Hill and shore; Angus Martin

- Gigha - A New Survey

The history of illicit distillation in Scotland has been recounted many times in a variety of publications. There have been romantic accounts of smuggling, of guerilla warfare against Excise men, and official reports giving the number of detections made, or fines levied on offenders infringing Excise laws. Ill-advised legislation was a major contributory factor in generating the tide of illicit distilling and smuggling which characterised Scotland in the early nineteenth century, when for more than twenty years the country endured all the excesses associated in modern times with the period of Prohibition in the United States of America.

Little or nothing has been known about the supply of equipment to the illicit distillers, hence the Still Books of Robert Armour are not only of considerable value but also of unique interest in this respect. The firm of Robert Armour, Plumber and Coppersmith, was established in Campbeltown, Argyll, in 1811. Armour was a well known name in Kintyre, and the family may have derived some of its initial capital from agriculture, from malting, and from distilling. The Report from the Commission upon the Distilleries in Scotland (1799) shows that one at least, James Armour, had been guilty of illicit distilling in the South Argyle Collection prior to 1798. (P.P. 1803:597-8). Colville (1923) refers to a licence, dated 1791, reproduced in The Wine and Spirit Trade Record, 14 December 1922, issued in the name of James Armour, Junior, and to another in the same name, dated 1796, which was preserved at Hazelburn Distillery, Campbeltown. Other Armours were connected with Meadowburn Distillery (founded in 1824) and with Glenside Distillery (1835), both in Campbeltown. The family, in company with many of the customers whom they supplied with distilling utensils, were Ayrshire settlers who came to Kintyre from 1650 onwards.

The Still Books were found among family papers, and they cover the period from May 1811 to September 1817. There are four jotters, now bound together into one volume of manuscripts, entitled Old Smuggling Stills, which forms a simple sales record. The only portion of the Still Books which is missing is some pages at the end of the second jotter.

Distilling in Kintyre

There was little or no practice of distilling in Kintyre prior to the seventeenth century; rent for the farm of Crosshill in 1636 included six quarts of aquavitae payable by the town of Lochhead (Campbeltown), but it is not clear that this spirit was distilled locally (McKerral 1948: 37-8) Distilling appears to have become well established by the mid-eighteenth century, although as late as 1772 whisky was described as 'a modern liquor', because in former times spirits had been prepared from herbs, and ale was in common use (Pennant 1772: 194). The activity experienced fluctuating prosperity depending principally upon changes in Excise legislation, and also on the availability of grain supplies.

About 1795, next to herring fishing, the distilling of whisky was the major industry of Campbeltown. The Statistical Account of Scotland (1794, x: 556) gives the following details:

Parish of Campbeltown, c. 1795

Location No. of stills Bolls distilled Produce in gallons In the town 22 5,500 19,800 In the country 10 2,134 6,350 32 7,634 26,150

The whisky was disposed of throughout the bordering highland areas, which 'brought profit to a few individuals ... but was ruinous to the community'. The parish minister advocated a duty so punitive that it would amount to a prohibition, and he commented on the situation: 'When a man may get an English pint of potent spirits or, in other words, get completely drunk for 2d. or 3d. many will not be sober' (S.A. 1794, x: 556 et seq.).

There were other disadvantages arising from distilling in the Campbeltown area, and elsewhere in Argyll. Recurrent scarcities of grain were troublesome: for example, Pennant noted that despite the quantity of bere raised, there was a dearth, the inhabitants of Kintyre 'being mad enough to convert their bread into poison'. distilling annually six thousand bolls of grain into whisky (Pennant 1772: 194). In 1782-3 the harvest failed and acute distress was caused among the poor of the burgh of Campbeltown. The Commissioners of Supply took steps to forbid the making of whisky, at the same time ordering all private stills throughout Argyll to be confiscated (Colville 1923). The distilling of whisky was again prohibited from 1795 to 1797 owing to grain shortages occasioned by the Napoleonic Wars. In 1812, there was another dearth of grain in Argyll. At that time. it was estimated that 20,000 bolls were converted annually into whisky in the country, of which over 50 per cent was being made illicitly in Kintyre, and over 30 per cent in Campbeltown alone (Smith 1813-15: 91).

Bere, or bear (hordeum sativum vulgare), a four-rowed type of barley, was grown in preference to any other crop for the express purpose of distilling. In 1811, bere was reported to form one half of the Hebridean crop acreage: it was 14 to 21 days earlier in ripening than other cereals, and required a growing season of 10 to 15 weeks. Seaweed was a sufficient manure, and bere was capable of maturing on poor soils in moist conditions (MacDonald 1811: 196). Much of the crop was wasted however, because of the primitive techniques of illegal malting which led to grain being steeped in ponds and puddles before being spread out on muddy fields, or in bothies or caves to germinate.

Farmers found a ready market for their harvest, and had quick sales among illicit distillers (P. P. 1823. Appendix 63: 172). Despite the spoiling of the crop during malting, such obvious gains were made in smuggling that the exportation of spirits seems at least to have paid for the import of cereals for food. Whenever legal distilling was brought to a halt, illicit distilling increased, and deficiencies of meal and flour had to be made good by importation.

In good years there were grain surpluses in Argyll, when bere and malt were available for export to the islands (P. P. 1803: 751). Conversely in Tiree, barley was a major export, followed by cattle and kelp, but from time to time, deficiencies occurred even there and imports were necessary (Cregeen 1964: 16 et seq.). It is clear therefore that in the more favoured areas of Argyll, bere for whisky-making was widely grown.

After 1817, when licensed distilleries began to be reestablished in Campbeltown, there were irregularities in the grain trade of the Burgh. Duncan Stewart, factor to the Duke of Argyll, resided there about 1822, and he was aware that Customs officials had often been defrauded by imports of barley being described as bere (P. P. 1823, Appendix 68: 188). As there were many registered malt kilns in the town, considerable quantities of bere were brought in for malting. Barley yielded more alcohol than did bere, but distillers and maltsters contended that they could not tell the difference between the two types of grain. Malt made from barley paid a duty of 2s. per bushel, whereas malt made from bere paid only 9d. per bushel. Hence when barley came into Campbeltown harbour from England or Ireland it was passed off to the Customs authorities as bere, and paid a lower duty. This reduction was intended to compensate for its smaller potential yield of sugars for conversion to alcohol.

About the year 1820 in west Kintyre, whenever the factors or agents for the lairds intimated that rent was due for collection, and specified a day, 'it frequently happened that the poor tenants had not converted a particle of the produce of their farms into cash'. In such a predicament the practice of the tenantry was to draw upon a Campbeltown maltster (known as 'the customer') who advanced a sum of money upon the promise of securing all the bere which the tenants could sell during winter and spring: the maltsters had their own agreements about the grain prices that were paid to the tenants (N.S.A. 1845: 390-1). Similar transactions took place in Kildalton, Islay, where the creation of a buyer's market, so unfavourable to the poor farmers, was deplored (S.A. 1794, XI: 296).

Attitudes of the Landowners

From 1786 onwards, there was a succession of enactments relating to the production of spirits in Scotland. Government attitudes to illicit distilling were uncertain. There was annoyance at the loss of revenue, concern at the social depravity and the profusion of dram shops, coupled with an inability to decide whether to give whole-hearted support to legal distillers in Scotland, or to secure revenue by severe restrictions on distillery operation. Obstructive regulations merely left the way open, albeit unintentionally, for the illicit distillers and smugglers to whom high duties were a bounty.

The 1798-9 Report alleged that landed proprietors in Kintyre even promoted private distillation, because they wished to receive their rents. Accordingly, smugglers could often count on the protection of partial Justices of the Peace, who were mainly landowners, if they were unfortunate enough to come before the courts (Smith 1813-15: 88). Duncan Stewart, Argyll's Factor, saw how the Justices modified fines to suit the circumstances of the people brought before them, otherwise the law would have been unworkable and the prisons overpopulated (P.P.1823, App.68: 188).

There was a determination on the Argyll Estates to suppress illicit distilling. Prior to 1772, the Duke of Argyll had attempted to discourage smuggling on his lands. He was reputed to oblige all his tenants to enter into articles to forfeit £5 and their still if detected, but the trade was so profitable that the people preferred to take risks (Pennant 1772: 194).

Until the levying of heavy still licence fees in 1786, farms in the island of Tiree had commonly at least one still each, producing both for local consumption and for export to neighbouring areas. A volume of 200 to 300 gallons of whisky was exported each year. The rents from the farms were largely paid out of the proceeds of these whisky sales. The crushing of the cottage industry of distilling brought some hardship to the islanders, and embarassment to the proprietor (Cregeen 1964: 16 et seq.).

In 1789-90, two legal distilleries were functioning in Tiree, which used locally grown grain, as well as supplies brought from Appin and the Clyde area, and imported coal. When grain was lacking in 1794, all distilling was stopped, but the tenants continued to make their barley into whisky illegally (op. cit.: 30).

The Duke of Argyll tried various methods in attempting to defeat the smugglers. He was primarily interested in increasing his rents, and as grain was a scarce and expensive commodity during the French wars, he stood to gain more by taking payments in kind, with a view to selling in mainland markets, than by taking payments in money. Illicit distilling defeated this purpose, making him the poorer, and accordingly very angry with his tenants. In 1800, for instance, he announced his intention of accepting rent payments in kind - the barley was to be surrendered on the pretext that this would prevent its being made into whisky. This policy did not meet with much success as in the following year no less than 157 persons were convicted before the Justices of the Peace on charges of illicit distilling (op. cit.: 50-3).

The Duke therefore insisted that the malefactors pay up every farthing of rent which was owing and determined to evict them if they did not comply. Furthermore, one out of every ten of the smugglers, 'the most idle and worthless', was to be deprived of his possessions and of the Duke's protection. It was difficult for the Duke's Chamberlain in Tiree to carry out these orders when compassion was aroused for motherless children and war veterans who would thus have suffered. Hence it was proposed that the tenants should be paid 40s. on their removal from the island, but there was a further mitigation. The initial offences had been committed in 1801, but the delinquents were still in Tiree in 1803 (op. cit. : 63).

In the interval, other instances of illicit distillation were detected. It was discovered that grain had been secretly shipped to Ireland to be distilled. There was also mounting unrest and opposition to the reorganisation of runrig: tenants had shown themselves ready to emigrate rather than conform. Even persons under summons of removal secretly contrived to work off a few bolls before their stills and worms were confiscated (op. cit . : 65 ) .

When improvements were attempted in Arran about 1814, there was similar opposition to letting in lots, and to road construction. Robert Brown, factor to the Duke of Hamilton, noted that people were especially defiant in districts where smuggling was practised (P.P. 1823, Appendix 63:166 et seq.). For instance, illicit distilling was of limited importance in the north of Arran because fishing was of greater consequence there, but elsewhere smuggling was common, and the tenants, like those in Tiree, were alleged to be in touch with the Irish. The lawless ones carried off the road tools, and began to break down new houses in course of erection. The Duke of Hamilton threatened to drive smugglers from the island (ibid.).

One remedy for illicit distilling was sought by establishing legal distilleries controlled by the lairds, who set up small licensed stills which they leased to tenants in order that production might be supervised. The local market for whisky would thereby be satisfied, thus removing a raison d'etre for the peasants possessing stills of their own, but care had to be taken that smugglers had no opportunity of retaining and converting their crop of bere into whisky. The Duke of Argyll was unsuccessful in setting up a licensed distillery in Tiree, since no-one could be found willing to undertake the making of whisky in a legal way, presumably because the legislative complexities made the venture unprofitable, and there was the risk of competition from smugglers (Cregeen 1964:54).

Other measures advocated included moderate duties combined with an improvement in the quality of legally made spirits, or, alternatively, the production of good ale. An 1811 review noted that an excess of grain was being exported from Islay to Kintyre, there to be converted into whisky, because Campbell of Shawfield, a proprietor in Islay, did all in his power to prevent illicit distilling and smuggling. He went so far as to build a brewery, the only one in the Western Isles, to encourage the drinking of beer (MacDonald 1811:617).

Habits were not readily changed and the people preferred strong spirits to ale (op. cit. 207). Lairds sometimes found that the desire to put down illicit distilling conflicted with the necessity of securing their rents. Argyll's factor wrote that 'in spite of all that an enlightened landlord can do, illicit distillation will be practised in the Hebrides as long as the present absurd regulations concerning the Scotch distilleries remain in force' (P.P. 1823, Appendix 68:168).

Legislative Changes

As Britain became involved in the wars of the late eighteenth century, the tax on excisable liquors increased. In the Highlands, the outcome was that whisky was prepared in stills of the small size permitted for private use, under the pretence of being solely for that purpose, and not for commerce. but the trade in whisky eventually passed almost entirely into the hands of illicit or private distillers.

Until 1786, the duty on whisky made in Scotland was levied on the basis of a presumptive number of gallons distilled from a known quantity of wash. At that date, an annual licence duty was introduced, based on the gallonage of still content, while the levy on malt used in distillation was partially remitted. As far as the licensed distillers in Campbeltown were concerned, the greatest disincentive came in 1797 when the licence duty was raised to £9 per gallon of still content in the Middle District of Excise in which Kintyre was situated. Legal distilleries thereafter ceased to exist in Campbeltown for a twenty year period - from 1797 to 1817 {Colville 1923). Meanwhile illicit distilling developed on an unparalleled scale, which is a sufficient commentary on the unsuitability of the legislation. The smuggling of illicit whisky became endemic throughout the Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland. Legal distillers were forced out of business; some of them took to illegal whisky making, while persons who had been accustomed to produce their own whisky for private consumption quickly saw the possibilities of marketing their production on a commercial scale and endeavoured 'to better their condition by having recourse to smuggling ... an unholy and unpatriotic traffic' (N.S.A. 1845:410).

In desperation, the Government of 1814 prohibited the use of stills of smaller capacity than 500 gallons in the Highlands. This measure signally failed to promote the establishment of large-scale licensed unit, and distilling remained underground. A year later the tax on stills was abolished, but instead a high duty of 9s. 4d. per gallon of spirit was imposed, which virtually cancelled out any benefit which might have ensued from the revision of the still content system of licensing. There were further changes until a wholesale revision was carried through in 1822-3, when an annual licence fee of £10, in conjunction with a modest duty on spirits, laid the foundation for the growth of the modern Scotch Whisky industry.

The Still Books of Robert Armour

The first nineteenth-century licensed distillery in Campbeltown was erected in the Longrow in 1817 by John Beith & Company (Colville 1923). Indeed a 'John Bieth', in association with others, was one of the regular clients of Robert Armour prior to 1817; his name figures several times in the Still Books. It is not unlikely that John Beith endeavoured to keep his craft active during the hiatus in legal distilling, and once conditions for legitimate trade appeared more reasonable, he obtained a licence.

It is regrettable that the Still Books cease in 1817 because it would have been useful to know whether Robert Armour's business was also deflected towards legality and whether he began supplying equipment to the new licensed distilleries which were set up in Campbeltown in increasing numbers from 1817 onwards, when there may have been less need for his services in an illegal capacity. Many Scotch whisky distilleries owe their origins to illicit beginnings. The names of some of the distilling families of Campbeltown recur throughout the Still Books - Colvilles, Fergusons, Greenlees, Harvies, Johnstons, Reids, Mitchells and Galbraiths, among others - as purchasers of utensils for private distilling (P.P. 1834:229; Wright 1963:486).

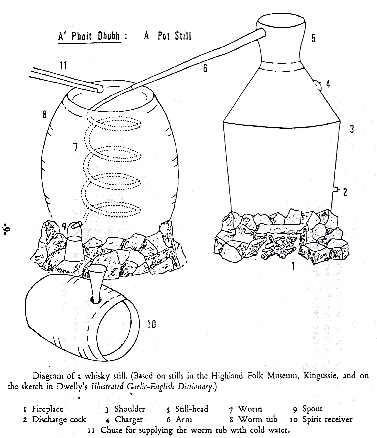

From the Still Books, it appears that Robert Armour, the founder, was the principal workman, although the employment of a lad is mentioned. Initially, the business was a small scale family enterprise which seems to have used the cover of a plumber's shop to conceal its principal function as a manufactory of distilling equipment, mainly still bodies, heads, and worms

(see Fig. 1).

fig. 1

Samuel Harvie

The first two pages of the Still Books read as follows:

August 16, 1811 To a body 23 lib. To a head 6 lib. 10 oz. August 21 To a body 13 lib. 8 oz. £5 6 3

Daniel Kelly Smith

August 21 To a worm 6½ lib. at 2/6 £0 16 3

Mary Kelly, Jene Taylor, Barbra McTagart, Lochend

Sept. 8 To a worm £ 1 :2 : 6 To repair a Body & Head 2 : 6

Archibald McKendrick, Mrs. Thomson, Widow Johnston, Florance Armour & Co. Longrow

August 29 To a body 13 lib. 8 oz. at 2/6 per lib. £ 1.13.9. " a head 5 lib . 6 oz. 13 . 4½ " a worm 9 lib. 1. 2.6 £3. 9. 7½ By cash from Widow Johnston £0. 10. 0 By cash from Arch. McKendrick 1.10.0 By cash from Mrs. Thomson 1. 0.0 By cash 1. 9. 7½ 3. 9. 7½

Alexander Craig, Nockniha

Sep 13. To going out to Repair a body 1 6 To copr. pack & Souther 2 lib 0 4 8 To a worm 11¾ lib. (By 2 lib. of their own makes 9¾ at 2/6 1 4 4

Oct. 4 1812 To cash for an old still 10 0 To cash for the ladd for nailes 6

Throughout the Still Books all entries have been heavily scored out, showing that payment was eventually effected, and in many cases this cancellation obscures much detail. The total value of work done, materials used, and goods supplied by Armour between 1811-17 amounts to over £2,000, representing an average turnover of £350 per annum.

At times, the coppersmith employed a code of letters to give details of income, and analysed cash receipts to keep a check on payments to account: for example from 16 May 1816 to 1 August 1817, he received £1148 11s. 7d. in cash, according to his reckoning. The average transaction only involved £2 to £3, and about 400 stills were produced.

The 1799 Report advocated stopping the supply of equipment to unlicensed distillers by making it impossible to have a still made or mended. Still makers, such as coppersmiths, would have to purchase a licence; the system would then confine illegal manufacture to 'tinkers and people of no capital and desperate fortune', who could be consigned 'to the house of correction', if discovered (P.P.1803:746). In 1797, when small stills were confiscated in Islay, the illicit distillers induced tinkers to come over from Ireland to fit up cauldrons and boilers as stills (ibid.). Failing these utensils, Aberdeenshire country folk employed kettles or pots to which a head was annealed. They were reputed to make good whisky, the quality depending not so much on the type of apparatus as on the skill of the operator in separating the optimum portion of the distillate for collection as potable alcohol (op. cit.: 760). Indeed, illicit whisky was renowned for its superior quality vis-à-vis the product of the legal distilleries. The whisky from Arran was even described as the burgundy of the vintages (Macculloch 1824:372).

The equipment constructed by Armour was simple, the still consisting of four parts - the vessel, head, arm, and worm.

The complete apparatus could be purchased for less than £5, and embodied about 30-40 lb. of copper, giving the pot a cubic capacity of upwards of 10 gallons. The still, head, and worm were the most valuable utensils, and the illicit distiller would use everyday household goods, like casks, creels, and measures which he had to hand. Many of Armour's clients must have owned more than one still, to judge by Samuel Harvie's purchases on the first page of the Still Books; there is evidence that the coppersmith provided numerous utensils for the same group of persons at a common address, so that each person must have had a still of his own.

There seem to have been two main sizes of still, some having vessels of 12-14 lb. of copper, and others of about 20 lb. It is conceivable that the larger ones would be utilised for distilling wash, and the smaller for distilling low wines in the second, or even third, distillation to yield whisky. Armour was also prepared to construct a tin still at a lower price to oblige a widow. He fashioned the head and worm of copper, and sold the apparatus for £1 15s. Tin stills would corrode rapidly whereas a copper still, if reasonable care was taken, could last for 20 years and more.

Besides making new distilling utensils, the coppersmith's business also consisted of trade in secondhand equipment; he valued old copper at 10d. per lb., while new utensils cost 2s. 6d. per lb. He carried out repairs both on his own premises, and at the houses of his customers, repairing worms, bottoming stills, 'sothering' (soldering) lugs, and fitting feadans. 'Feadan' is Gaelic for a whistle, and is the spout or valve fixed to the end of the worm, where the distillate emerges. In addition, Armour made branders, flacks,* fillers, cans, nails and other hardware, which if orders were frequent and to a large amount, he sometimes gave away for nothing. Entries show that he 'gave a filler 1s. 6d.' or 'gave them a pint can 1s.'. He even stocked copper tea kettles both new and second-hand, but these may well have been much less numerous in Kintyre than private stills.

- Brander: a gridiron,

- Flack or 'flake stand': the cooling vessel in which the worm is immersed,

Armour's customers normally operated in groups of 3 to 7 forming a 'company', whose names are carefully recorded in the Still Books. Indeed, ownership by parties of tenants was common in Easter Ross, as well as in other parts of the Highlands (S.A. 1793, vii: 258). The Still Books, however, give a better and more accurate account of the organisation of illicit distilling than has hitherto been available. It may be that the loss of capital equipment owing to detection would be less disadvantageous if it were vested in a group operating together. Writing of Harris and Lewis, MacDonald noted that the people frequently joined together to pay the fines exacted by the Excise authorities (MacDonald 1811: 809-10). When a J. P. court was held at Stornoway in July 1808, the crofters paid 'pretty smart fines', before returning to their homes grumbling and discontented. The fines however were divisible in consequence of private compacts agreed among several families, and hence smuggling and distillation were soon resumed (Ibid.).

With a group organisation, the private distillers would be able to move their installation from one hiding place to another with considerable ease, and of course, they would spread the burden of the initial capital cost among themselves. This type of arrangement may have facilitated the raising of capital to enable individuals in a 'company' to purchase their own equipment. As distilling was a protracted process, perhaps taking three to four weeks from malting to the final distillation, there would be sufficient persons to take turns in carrying out the various operations.

An examination was made of 200 consecutive transactions relating to the acquisition of stills from Armour, with a view to establishing the nature of his clientele. One hundred of these transactions concerned men only, either as groups or individually. The illicit distillers in Argyll were generally small tenants. What is surprising about Armour's business, and hence about illicit distilling in Kintyre, and probably in other areas of the Highlands, is the large proportion of women engaged in making illicit whisky on their own account. Farmers seem to have delegated the task to maid servants and other 'inferior persons', who acted as covers in order that more substantial individuals would escape detection (P.P. 1823, Appendix 63:166 et seq.). Perhaps illicit distilling was regarded as part of general domestic duties, or as a source of pin money, especially for widows or single women, for whom it may have been a ready source of income. Women have an honourable place in the history of distilling in Scotland; Mrs. Elizabeth Harvie was a distiller in Paisley, whose descendants subsequently moved to Port Dundas, Glasgow, setting up Dundashill Distillery, and Mrs. Cumming was owner of Cardow Distillery on Speyside. No fewer than 58 of the series of purchases involved women, either singly or more commonly in a company. Mixed groups, numbering 42 in all, made up the remainder in the sample. The men may have been more occupied with fishing and agriculture. Only 20 per cent of these purchases of utensils revealed one individual operating on his or her own account; to judge by the relevant entries in Armour's Still Books which indicate the buyer's occupation, e.g. cooper, flesher, wright, farmer, miller, shoemaker, or innkeeper, these illicit distillers were persons of substance.

Prior to 1823, when smuggling was a lucrative trade, a substantial number of cottagers and labourers in Kintyre were said to support large families on the profits of the business. A professional private distiller could clear 10s. a week after all his expenses were paid (Bradley 1861: 7). Early marriages were frequent as a wife was an indispensable part of the enterprise; much of the work was assigned to women who were 'fit for, or employed in nothing else' (ibid).

The financial standing of Armour's customers is disclosed by the manner in which they settled their accounts. The clients occasionally paid up when they collected the utensils, or else made a down payment, followed by several installments, perhaps taking two or three years to clear off the debt. Credit was normally of 4 to 6 months duration. Payments in kind were remarkably rare, less than 1 per cent of all transactions recorded in the Still Books showing settlements in cart loads of peats, meal, potatoes, cheese, butter, and, of course, whisky.

An account for goods supplied to John Beith, and others at 'Dalinrowan', Campbeltown, amounting to £5 7s. 6d., was partly paid 'By 2 pints and 1 mutching (mutchkin) strong whisky at 10/- per gallon'. The references to whisky show that its price fluctuated wildly, varying from 1s. 3d. to over 9s. 6d. per pint, which may reflect grain prices, the scale of operations, and the quality of the product.*

* In the Still Books, references to the price of illicit whisky on the black market are very rare; hence it is impossible to construct any meaningful list of price movements,Some smugglers would fill pint casks at 2d. a gill. The whisky was then retailed at dram houses attached to much frequented places, like mills or smithies (Smith 1813-15:91). In the post-1815 depression, the price of grain fell by 50 per cent in seven years; this brought advantages to the smugglers, giving them a bigger profit margin on their whisky, because its price did not fall by a corresponding amount. In 1822. the price of illicit whisky in Kintyre was 10s. to 12s. per gallon at 20· over proof, and it was worthwhile conveying it to the Ayrshire coast, and even up the Clyde to Glasgow in fishing boats and coasting vessels (P.P. 1823. Appendix 63:172).

There are notably few instances of bad debts in the Still Books. All transactions seem to have been settled, to judge by Armour's crossing out of the appropriate entries. Notes regarding promises to pay are very rare -

'The above persons have granted their lines (liens) each for their own part to pay the above sum ....'In places distant from the Burgh, securing payment could be awkward. One still was supplied to Whitestone, Saddell, for the use of four partners two of whom had to promise to pay before they could take delivery.

We the undersigned do acknowledge having received for the mentioned persons above copper work ... amounting to Three Pound Eighteen shillings Sterling & will pay the same on or before the 20th Novr. 1815.

Witness our hand: Edward Langwill

Jamy Stewart

his

X

mark

There is much evidence of consumer loyalty, which must indicate satisfied customers. A company, who were regular clients, bought a secondhand still, and head with an old worm, in September 1813, and were back for a new still of 17½ lb. in December of the same year, and for another worm in the following January. Armour was obtaining orders from the same groups, or individuals, four to six, or more, times a year throughout the period 1811-17. This fact alone must disclose the profitability of illicit distilling, and the intensity with which the utensils were being used.

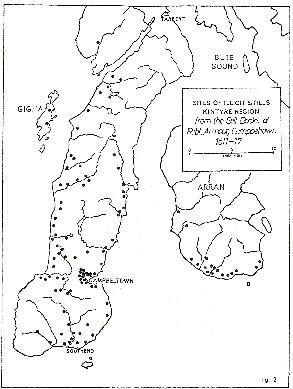

The area supplied with stills from Armour's workshop was a far-ranging one. He was not the only coppersmith in the Burgh, but the majority of the utensils - more than 40 per cent of those manufactured by him - were installed in and around Campbeltown itself: Lochend, Longrow, Dalinruan, Dalintober, Bolgam Street, Corbet's Close, and Parliament Close figure repeatedly in the Still Books. Armour distilling apparatus was also sent to places as far north as Clachan in N. W. Kintyre and as far south as Machrimore and Pennyseorach in Southend. He exported equipment across Kilbrannan Sound to the south west coast of Arran. Another island where Armour did business was Gigha. It has been possible to identify and plot the approximate sites of most of these illicit distilleries on the accompanying map; and practically all of them show common locational factors, such as the presence of burns, and proximity to coastal areas.

The coppersmith was willing to replace equipment seized by the Excise authorities while being transported from his shop; for instance, he recorded on 25 August 1815, that a client had 'the first Body, head & worm seized nigh Smerby, and I allow myself to give something down of it'. This particular order was being conveyed to Arran. It is said that the assistance of women with cloaks over long and voluminous skirts was especially helpful when stills were being collected, whereas men had to carry the stills in sacks.

In the distribution of illicit whisky the smugglers operated in bands, and were bold enough to deforce Excise officers on occasion. Crofters and fishermen were known to overpower a whole crew of Revenue men, to carry off their oars and tackle, and set them adrift in their own boats (Gordon Cumming 1883:286; N.S.A. 1845:450). The 1799 Report described how the country people were 'disorderly and tumultuous', so that no Excise officer could carry out his duties among them, without being 'obstructed, insulted and beat' (P.P. 1803:788)' The Board of Excise had inadequate resources of manpower and finance to police the region: Excise men were often strangers, with tenuous local knowledge, and hence the ability to 'jink the gauger' was not hard to acquire. Robert Brown, Hamilton's factor, showed that the tenantry in Arran could behave like banditti. He averred that the officers on the island were so lax that he had to send his own men to Arran to seize stills, 'to a very great number', in the course of a day.

During the foray, the factor's party gathered in thirty stills or more, but the Excise men only found six. Indeed, the officers did not appear anxious to effect seizures (P. P. 1823, Appendix 63:166 et seq.). Captured stills were a source of income to Excise men, because they were paid for their confiscations and they also derived profit from the fines levied on delinquents. Bribes were known to be paid to them in the guise of presents or loans.

The virtual prohibition on small scale distilling in the Highlands made it, and its concomitant, smuggling, respectable occupations. Those who were caught were not criminals, but debtors to the revenue, and could stay in prison in relative comfort being allowed a day maintenance. The Excise authorities were misled by false information, and confounded by names and language difficulties. The temptations to perjury were almost irresistible.

Besides having a reputation for lawlessness those engaged in illicit distilling were regarded as unpunctual in paying rents, which were also usually deficient. Robert Brown, Hamilton's factor, was prepared to dispossess smugglers because they were rarely enterprising farmers - they sat up all night and skulked by day (ibid.). He alleged that they consumed too much of their product, neglected their families, their land, cattle, fishing, and kelp gathering. Distilling and smuggling seem to have been the chief employment of crofters and fishermen in winter (N.S.A. 1845: 450).

Conclusion

After 1823, and the major legislative changes which then took place, many of the enterprising illicit distillers began to take out licences, and a profusion of new legal distilleries developed in Campbeltown, and in other regions of Scotland. Nor did Armour's customers turn their skill to legitimate trade only in Kintyre. Colville mentions letters which came from settlers in Ohio about 1825 in which Campbeltown emigrants were reported to have found employment in producing the same kind of whisky as they had formerly made in the Burgh (Colville 1923).

By the mid-nineteenth century, the great staple industry of Campbeltown was the distilling of malt whisky. Smuggling was almost completely suppressed in Kintyre (N. S. A. 1845: 464; 315). Likewise in Tiree and Coll illicit distilling was unknown (N.S.A. 1845: 209).

The coppersmith's business remained in the hands of the Armour family until 1948, and although the ownership changed at that date, the original name was. Armour's Still Books survived because they had been well concealed in a bureau at the office in Campbeltown. It is disquieting to imagine what effect the discovery of this stock of information, involving over 800 separate transactions, would have had if the Still Books had come into the possession of the Excise authorities prior to 1822. There must have been a strong element of collusion, a bond formed of mutual dependence and interest between the coppersmith and the illicit distillers: on occasion the Excise officers may have been implicated.

Robert Armour must have been typical of many coppersmiths and plumbers in distilling areas. The modest transactions recorded in his Still Books reveal the existence of a multitude of illicit enterprises, small in scale, but certainly ubiquitous, which involved people of the most varied social background, women as well as men. It is clear that illicit distillation attained the dimensions of a domestic industry, a fact which has tended to be underestimated in the economic history of the Scottish Highlands.

REFERENCES

Printed Sources

- BRADLEY, E. (CUTHBERT BEDE); 1861 Glencreggan. London.

- COLVILLE, D. ; 1923 The Origin and Romance of the Distilling Industry in Campbeltown. (A paper read to Kintyre Antiquarian Society, 10 January 1923, subsequently printed in The Campbeltown Courier 20 Jan. 1923

- CREGEEN, E.R. (ed.) ; 1964 Argyll Estate Instructions, 1771-1803. Scottish History Society, 4th series, vol. 1.

- GORDON CUMMING, C.F. ; 1883 In the Hebrides. London.

- MACCULLOCH, J. ; 1824 The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland, vol. 4. London.

- MACDONALD, J. ; 1611 General View of the Agriculture of the Hebrides of Western Isles of Scotland.

- MACKERRAL, J. ; 1948 Kintyre in the Seventeenth Century. Edinburgh.

- N.S.A. 1845 New Statistical Account of Scotland, vol. VII (Argyll). Edinburgh.

- P. P. Parliamentary Papers

1803 The Report from the Committee upon the Distilleries in Scotland, 1798-9. XI. London

1823 The Fifth Report of the Commissioners of Inquiry into the Revenue arising in Ireland, etc. VII. London.

1834 The Seventh Report of the Commissioners of Inquiry into the Excise Establishment. Appendix 67. XXV. London. - PENNANT, T. ; 1772 A Tour of Scotland and the Western Isles. Chester

- S.A. Statistical Account of Scotland, ed. Sir

John Sinclair. Edinburgh

1793 Vol. VII 'Parish of Urray' pp. 245-59.

1794 Vol. X. 'Parish of Campbeltown' pp. 516-67.

1794 Vol. XI 'Parish of Kildalton' pp. 286-97. - SMITH, J.; 1813-15 General View of the Agriculture of the County of Argyle. Edinburgh.

- WRIGHT, H.C. ; 1963 'Springbank Distillery, Campbeltown, (Proprietors, J. & A. Mitchell & Co. Ltd.)' in the series 'Scotch Whisky Distillers of Today.' The Wine and Spirit Trade Record, 17 April, pp. 486-90.

MS Source

- ARMOUR MSS ; The Still Books of Robert Armour, Campbeltown, are in the possession of Mr. R.R. Armour, 14 Braehead Road, Edinburgh, by whose kind permission they were made available for consultation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Glen and to Professor Alexander Fenton of the School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh, for permission to publish this paper, which originally appeared in Scottish Studies, vol. 14 (1970), pp 67-83. In her original article Dr. Glen gratefully acknowledged the generous assistance afforded her by the late Mr. Duncan Colville.

We wonder how many of our readers recognise ancestors among Messrs Armour's customers?

Mr. Thomas ("Mack") McLarty, Chief of Staff to President Clinton, has replied to our enquiry admitting Scottish ancestry but uncertain as to a Kintyre connection. He says that judging from the number of letters he has received from allover the U.S.A. the McLarty name is well represented in that country.

A.I.B. Stewart

The Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages in Campbeltown holds an interesting Register of births from 15 September 1794 to 10th January 1820. This volume appears to contain records of births to members of both the Highland and Lowland congregations.

It is not known who kept the Register, but during the period covered the keeping of such records was within the province of the Kirk. There were no civil registrars before 1855. The Register gives the name of the child, of the father and the mother, together with the date. Its value is somewhat diminished by the fact that there is no further identification, such as an address or trade or profession. But in an Appendix to the Register there are two most interesting lists.

The first is as follows:

"Names mentioned in this copy of Register believed to be changed and now known by the surnames stated in the following lists."

McFail to McPhail;

McPhater to Paton;

McFater to Paton;

Loynachan to Lang;

O'Loynachan to Lang;

McKendrick to Henderson;

McConachy to Duncanson;

McSporran to Pursell;

Mcllchere to Sharp;

McMichael to Carmichael;

McMath to Mathieson;

Drain to Hawhorn;

McQuilkan to Wilkinson or Wilkieson;

McGrath to Love;

MCllchattan to Hattan;

McGeachy to McKechnie;

McIlreavie to Revie;

McTavish to Thomson;

McWilliam to Williamson;

Forrester to Foster;

McKeich to Keith;

Brodelty to Bradley;

Brodley to Brodie;

Brolachan to Brodie;

O'Brellachan to Brodie;

McLarty to McLaverty;

McEachran to Cochran;

McKinven to McKinnon;

McKinnvine to KcKinven;

Kiergan to McKerral;

McComish to Thomson;

McTavish to Thomson;

McKlargan to McKerral;

McGildownle to Downie;

McIldownie to Downie;

McMurchy to Murchie;

McMurchie to Murchison;

Mcllbride to McBride;

McIlvoil to McMillan;

McCuistan to McQuistan;

McKergish to Ferguson;

McVorran to Morrison;

Mcllvray to McGilvray;

Mclntagart to McTaggart;

McLaverin to McLaren;

Menish to Menzies;

Langlin to Langlands;

Conolley to Conley;

Toss to McIntosh;

Buy to Bowie or Buie;

McShenoig to Shannon;

McGawly to McAulay;

McPhadden to McFadyen;

Pheder to Vetters

There follows an additional note as follows:

McEown, McEuine, McEwan, McEwne, McEwen; the same as McEwing

Hewie - Howie - Hewen; the same as Huie

McDuffie the same as McFie or McPhee; see 8 October 1808, 31 August 1811 12th March 1813 & 5th March 1814.

McRoln, McCallum, McColm Malcolm, Maholme - the same name; see 28 Jany. 1796 - 19 Feb 1798; 30 January 1798 - 14 November 1802.

McLeize, McIlleis, Gilles and Gillies the same; see 12 Sept 1800, 13th October 1802, 27 May 1804, 25 January 1805 and 31st July 1806.

Barklane, Barkley, and Barclay; the same name.Finally there is a List headed "Christian names changed" , as follows:

Euffen, Effy to; Euphemia

Finnel to; Florance

Iver to; Edward

More to; Marion

Girsel, Grizel to; Grace

Betty to; Elizabeth

Giles, Jealise, Gielles, Jeilley to; Julia.

Copyright belongs to the authors unless otherwise stated.

It organises monthly lectures in Campbeltown - from October to April, annually - and has published its journal, 'The Kintyre Magazine', twice a year since 1977, in addition to a range of books on diverse subjects relating to Kintyre.

CLICK HERE for Correspondence and Subscription Information.

ISSN 0140 0762