THE KINTYRE

ANTIQUARIAN and

NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY

MAGAZINE

Issue Number 56 Autumn 2004

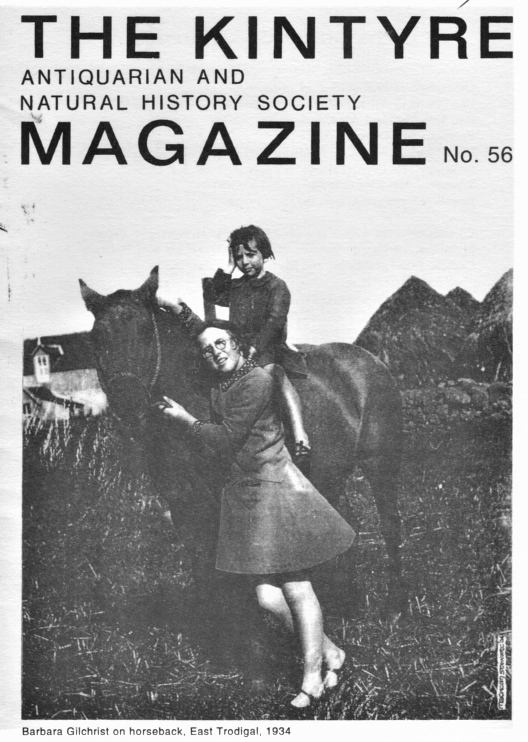

Barbara Gilchrist on Horseback, East Trodigal, 1934

CONTENTS

- Growing up on a Machrihanish Farm: Part I; Barbara Malcolm

- A Ship Full of Hope; Pat MacDougall MacLachlan

- James McNiell Whistler

- Letters from Australia; Robert Douglas

- By Hill and Shore; Angus Martin

- The Dispersal of the Brown Family of Kerranbeg and Machrimore, Part III;Graeme Reynolds

- Kintyre, North Dakota, Centennial: 1904-2004

- Nature Notes from North Kintyre; Ann and Ian Baird

Barbara Malcolm

Old folks are often accused of seeing the past through rose-tinted spectacles, but I don't recall a time when I was unhappy with my place of birth. East Trodigal Farm is about half-a-mile from the Atlantic coast with its five-mile stretch of sand and some of the most dramatic sunsets seen anywhere. The changing light and moods of the sea have always held interest; so too the strong winds and occasional fierce storms.

In my youth, East Trodigal was a small mixed dairy farm, at first tenanted by my father, Duncan Gilchrist, and later owned by him. When the farm was put up for sale, my great-uncle John, who had farmed Corran and retired to Lochend House in Campbeltown, stood security - a fact my Father encouraged us to remember. There were no grants or loans without backing then. I am called after great-uncle John's wife, Barbara McMillan Gilchrist.

Father's mother, Mary McNicol, lived at Mingary, a rented croft in the hills above. Despite having neither telephone nor radio, she was very content. Provisions were taken up by horse and cart and one of my older sisters, Jean or Mary, provided company at week-ends. My main memories of this granny were her home-made nettle soup and her use of honey on wounds.

The farm employed two workers who lived in the bothy, a live-in maid, part-time shepherd, as well as hand milkers. Casual labour was needed at busy times. During the agricultural workers' strike in August, 1935, my father collected the milkers and barricaded the byre door. I found the noisy scenes outwith a bit frightening!

Farms then were more sociable places, especially when there was shared help from other farms during harvest and when the big mill came to thresh. Much banter took place over the dinner table. When I was very young, Mr John McKay, who didn't live in, was ploughman. Inquisitive small fry weren't welcome in the stable, where the men had their smoke after dinner. Being an enthusiastic cigarette-card collector, I befriended smokers - all gents - and filled several albums: wild flowers, film stars and the Royal family are a few I remember.

During harvest, mid-afternoon sustenance was sent to the field .freshly-baked plain and treacle girdle scones, pancakes, fruit loaf or gingerbread. Plain wholesome fare was the order of the day. The liquid taken throughout the day was water to which a handful of oatmeal was added. All of us had porridge and cooked breakfast, with a slice of plain bread toasted in front of the range using a toasting-fork. Dinner at mid-day consisted of soup followed by a meat, fish or cheese course with potatoes and vegetables. The meat and vegetables were often cooked in the soup-pot. On wash day, one course - boiled rice pudding or thick potato soup - was eaten. Cheese was freely available and the men ate stacks of plain bread. The only tinned foods I recall then were tomatoes, corned beef, salmon and fruit. Puddings were reserved for Sundays and tinned fruit was a novelty. Tins were for emergencies.

Owing to the low price of milk in the '20s and '30s, cheese-making was revived. Most farms made Dunlop cheese from spring until autumn. In the late 1920s, Mr Andrew Hamilton was involved ill the building of a new piggery. The whey from the cheese vat in the dairy was run underground and received in a container in the piggery.

During the school year our family had our mid-day meal in Lavery's tea-room in Longrow South, where we had an excellent two-course meal - no puddings - for 3d. On arrival home, we had a plain tea with maybe a tomato or banana. Gradually, in the '30s, high teas - poached or scrambled egg, fish, cold meat or salmon with salad - were introduced. Lettuce at that time was looked on by many as a food more suitable for rabbits than humans.

From accounts, my late Mother, Jeanie McDonald - brought up at Chiskan Farm - was a good-looking, talented woman and a keen SWRI member. I remember pot bulbs in the spring - a less common sight then, than now. She did some fine drawn-thread table and bed linen, as well as painting in oils. During the early 20th century, before I was born, the family moved into the cheese-room in the summer months and the farmhouse was let with attendance. Mr Robert Gemmell Hutchison, R.B.A., R.S.W., whose paintings now fetch considerable sums, was one occupant. His subjects were often interiors and seascapes with children. He painted sister Jean and one of the Hamilton family who lived in the cottage, neither of which paintings I have been able to trace. Much of his work is said to be in private collections. I have one of his prints looking towards Westport with a young girl on the Duan, where the caddies congregated. P MacGregor Wilson, R.S.W., not so highly rated, was another visitor. One of the Machrihanish villas, Golf Villa, was purchased for letting purposes. Later in the '30s it was re-named Innerora; it is now Minard House. Use was made, by my Father, of the Ford Soft Top to take visitors for runs.

Most of the villas were owned by city-dwellers and let out or occupied by the owners during the summer months. Winter residents were few. The Rae family owned Ardell and Lizzie was joined by her sister and family in the summer. Dr Kay lived at Rothmar prior to its being destroyed by fire, and, after the Second World War, rebuilt as two houses. Mr and Mrs Smith of the Ugadale Arms Hotel stayed part of the winter at Westcliff (now the Anchorage) and Miss Greenless, next door, was a winter resident. The present men's clubhouse was owned by an Edinburgh family, the Paulins, who came for August and September each year and let during earlier months.

Pre-war, the Ugadale Arms had many regular visitors, e.g., Lady Astor and family, usually referred to as 'gentry' or 'toffs'. Employees came from the city and were sometimes talked of as 'hotel skivvies'. It was fascinating to see the ladies in evening dress and the men in dinner suits (unusual then) at the front door of the hotel. On a nice summer evening, some of the gents would stroll along the road after dinner, puffing their cigars. There was a yearly golf match between locals and visitors and a yearly concert arranged in the Village Hall, when we were given a rendition of 'It's nice to get up in the morning'.

Mr Jimmy Kerr, golf c1ubmaster, Miss K McPhail, and the family of Mr McPhee, greenkeeper, who lived behind the Clubhouse (now The Beachcomber), were winter residents, as well as Miss Campbell in one of the cottages near the shop. The shop, which was owned by the Livingstone family - Susan and Janet - had very restricted stock, even more so in wartime: cigarettes, biscuits, sweets, lemonade and postcards. Janet ran the shop and was seldom low on butterdrops or peppermint imperials! For many years there was a large faded packet of 'Players' cigarettes in the front window - 20 for elevenpence ha'penny - and a postcard, of the pull-out variety with local views, in the little side window: 'It's lonely, dear, without you here at Machrihanish.' This feeling I sometimes had prior to the visitors' arrival in the early summer and when they had all departed in the autumn. Janet dressed all in white - head to toe - in summer and all black in winter. I remember being startled on meeting her at dusk in Lossit High Glen.

Part of Craigmore was occupied by a Lossit Estate employee and family. The Post Office was run by Mr Sam Wilson, who made his own ice-cream for sale, and later by the Anderson family. All the villa-residents beyond were owner-occupiers. I remember Miss Fleming, who had Machrihanish House, used to cook boarders' kippers in the wash-house, owing to their pungent smell.

Three privately owned houses (one owned by Donald Fraser and let, Mr Mathers and family and Mr T Mitchell) were built behind the Village Hall in the mid- to late '30s, as well as four council houses (McGown, Kelly, Irvine and Paterson families) and a double villa (McNeill family and Miss Gilchrist) beyond the original villas. Families (McMaster and Stewart) lived at the Old Pans, though the building - subsequently demolished - was in a poor state of repair. Donald Fraser, gamekeeper to the Macneals of Lossit, lived at Lossit Gate with his wife Bella. He was a frequent visitor to East Trodigal on Sunday evenings and had a fund of stories, old and new, some of which had to be taken with a good pinch of salt. Whoever was most in favour received the yearly sprig of white heather. Mr and Mrs John Wylie were at the entrance to Lossit Park. He was a fisherman and she a schoolteacher and keen guider. I didn't get far beyond the gardeners' cottages and High Lossit Farmhouse.

The Girl Guides met in the gun room at Lossit House. It was a well-attended group, but by the late '30s no replacement leader was found for this troop - the Purple Ties and Wild Flower patrols. I had a trip to Edinburgh and saw King, Queen and Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret. We also had a camp at Kilmelford - a bit wet there, but good fun.

My father was an Argyll County Councillor for nearly 20 years. His main interests were employment, housing, roads, hospitals and law and order. Had there been choice, engineering would have been his. Grandfather Gilchrist, manager of Killean Farm, died a month before his son's birth in 1880. Father's other interests were golf, bridge and bee-keeping. During the Second World War he took up butter-making. Toby Munro, son of Polly, who milked for us for many years, was his chief assistant. A miniature high-walled orchard, where the bees were housed, was built in the late '30s.

I started in Campbeltown Grammar Primary School in the autumn of 1930, the year the 'Wee Train' was replaced by a bus service, which was relatively frequent. On a good summer Sunday, innumerable buses poured in and out from Campbeltown. With four girls in the family, the arrival of young brother John in October resulted in much celebrating. I was only allowed to whirl him out once in the pram, which I coped. It was a high model and was duly replaced. It wasn't done with intent, as John and I got on well. Our few fights were sufficiently violent to be memorable. He was a cute wee fellow, though, were he around today, he'd disapprove of my saying so. At one produce show, when Trodigal got second prize for their bag of oats, John attempted to change the ticket for the first. At that time, the show had a large number of exhibits in the baking and preserves sections.

Local people took advantage of available self-catering cottages. The late Mr Campbell Mitchell, local dentist, and his family, took the Hotel cottage for the month of June. The McMurchy family took it in July. Betty (now Mrs Leech) was my era and her older sisters were ages with mine. We used the wash house to change for swimming in the small bay below the hotel, being our favourite, and a safe area. On surfacing, a chittering bite - usually a tea biscuit - awaited. Mr Willie McMurchy, a keen amateur dramatic enthusiast who often took part in local concerts, had great patience with children. He made a raft using empty oil-drums, from which we could jump or dive. A number of youngsters took up golf using cut-down clubs - wooden shafts then. It was a great advantage to have the nine-hole ladies' course, where children could practise without annoyance to others. There was a yearly children's competition when everyone got a prize - some second-hand - donated by members. I much preferred a golf ball or a few tees to Winnie the Pooh!

Pre-school, as mother was fully occupied, I spent a lot of time with my father in what he described as the 'Ingin Hoose', where he did regular machine and car repairs. A bit of wood, hammer and a few nails seemed to keep me happily occupied. As the concrete floor of the farm kitchen rarely allowed a china doll more than twenty-four hours' survival, my interest in dolls was quickly lost. Board and card games were more my scene. Dolls' tea-sets seemed to last much longer - interest in -food started early.

On one occasion, when, at a loose end, I packed my case and set off towards Campbeltown, Mr Donald McCuaig, a local gardener from Drumlemble, turned me around at Kilkivan. There was another notable occasion when I accompanied Father to town. In the Main Street entrance to the Argyll Arms Hotel there was a form attached to one wall, where I sat, directly opposite a door leading to the bar. Much laughter followed, when, on arrival home, I announced that Pop had been in a place with the first three letters of my name!

Later in the '30s, being himself not averse to a dram, my Father was able to empathise with our minister at Casllehill, reputed to over-imbibe, which was frowned upon by elders, who withdrew services. This resulted in father having to be at the plate every Sunday for some weeks. One of my weekly tasks was to wash the car - an Austin 10, SB5135 - in readiness for church-going. The job had just been completed when I heard a voice saying: 'To Hell - A'm havin a rest the day.' Not a complete 'Holy Joe'!

The original coal-mine nearby never operated after the 1926 strike. My father purchased what remained, sold ashes from the bing (heap) for 6d per cart and built Cloverpark, to which my Granny moved from Mingary around 1930 and which, after her death, was used for monthly, or longer, lets. Families returned year after year. The Careys, who had local connections, had a long winter let. I mastered the art of cycling on the boys' bikes. Mr Carey was a diplomat - a silver threepenny piece was often the reward for delivering the milk. We didn't see too many of those, except maybe on Fair Day, when Mr Hendry Barbour, Dalrioch Farm, came up trumps. Cloverpark became the office of the mine which opened in 1946. Two semi-detached cottages were built at the site of the original mine, aptly named Ashbank by Sarah Gillespie (later Mrs Sandy Henderson) who was with us at that time.

Drastic changes took place in June, 1933, when we lost my Mother and a fifth baby daughter. It had been a glorious June week, but no interest at all was shown in my finds on the shore on three consecutive days after school - a slim black 'Swan' fountain-pen, a half-crown and a silver pen-knife.

My father was seriously ill with pneumonia at the time. When Nero, the collie, who was never indoors, found Father's bedroom he lay on the mat at the door throughout his illness. It would have been a brave person who tried to move him. Many years later, Meg, whom we had when Father died, went completely off her food and seemed to exist on nothing.

In August, 1933, we got our first radio, but it was 1937 before a telephone was installed, a shared line - one ring for Ugadale Arms Hotel, two for Westcliff and three for us!

Owing to illness at home, John and I were: packed off to stay with my Grandmother and Aunt - Mrs Catherine and Miss Bessie McDonald, primary teacher - on Kilkerran Road. Grandfather, Sandy McDonald - a likeable man - had died a few years earlier. No one could have dreamt up worse punishment than separating me in the summer months from Machrihanish with its lovely clean beach with no litter, only the occasional sought-after dark-green or clear glass ball, used as markers for lobster-pots. The stony beach on Kilkerran Bay had little appeal for bathing and we were without companions. Contentment had to be found in the garden. Reprimands were not unknown, especially on the day when, visiting at home, I spent my return fare on a delicious 'slider'.

1 enjoyed school, the attractions being the company and sport. Elsie Black, Flora Campbell, Cathie McNeill, Margaret Grant, Margaret McKillop, Renee Mitchell and Margaret Blue were a few in my year, some of whom are no longer with us. Hamish McIntyre, Duncan McIntyre, Duncan McConnachie, Hamish Armour, Duncan Brown, John Short, Archie Cook and James Macdonald were among the boys. I was not a reader - a drawback in later years - and had a much greater affinity with figures than words, facts than fairies.

TO BE CONTINUED

COVER ILLUSTRATION: Barbara Gilchrist on milk recorder's pony at

East Trodigal Farm, with sister Cathie, 1934.

Pat MacDougall MacLachlan

We have heard a lot in recent years of the sinking of the Titanic in 1912; but few people commemorate another sea tragedy just a generation earlier, one that touched my own family very closely, when an emigrant ship was lost 400 miles south of the Cape of Good Hope in terrible circumstances.

My grandmother, whose first cousin was on board with his wife and young children, could I'm sure have told me everything about it, for the whole family must have been devastated. But she died when I was ten, and I didn't give much thought to 19th century forebears until even my parents' generation - who still might have told so much - had gone beyond questioning. All I did know was that many of them lie in the old burying ground at Killean, beside the ruined kirk, about 18 miles north of CampbeItown. They include MacDougalls, Curries and Thomsons, my grandparents and great-grandparents, great-uncles, great-aunts and cousins; and among their graves no memorial is more arresting than the Thomson stone, which you come on just inside the gate. It records John Thomson, 'late miller and joiner, Glenbarr', and his wife Sarah Currie, who was my grandmother's aunt; and below them:

HIS SON JOHN AGED 38 YEARS

HIS WIFE BARBARA BLACK AGED 35

& THEIR CHILDREN

EPHEMIA,7 LACHLAN,5 JOHN, 3

SARAH, 1

ALL OF WHOM PERISHED AT SEA 19 NOVEMBER 1874

IN THE ILL-FATED SHIP "COSPATRICK"

I wanted to know so much more. This is their story, which many people helped me to put together.

On September 11, 1874, a beautiful sailing ship set out from Gravesend Docks in London bound for Auckland, New Zealand. Originally built in India, of Burma teak, for some years the Cospatrick had been used as a troop-carrier under Captain Elmslie. Then, after her owner died, she was bought by the Shaw Savill Line and, still under the command of Captain Elmslie, began a new career as an emigrant ship. She had already made one voyage to New Zealand in this capacity.

The Cospatrick was a fine-looking ship, full-rigged, with three masts each able to set a mainsail, topsail and topgallant, as well as a jib and forward stay-sails and a spanker aft. And she was a ship with a cargo of hope: she carried a crew of 43, her captain's wife and young son, four independent passengers and 433 emigrants - very few of them over 40 years old - on their way to a new life far from everything they had known. A passenger list, put on the internet by Denise and Peter Wells of New Zealand, breaks one's heart with the pathos: many were young parents with their children, little boys and girls and babies; others were single, and the older folk were on their way to join family members who had already emigrated. They came from Scotland, from England, from Ireland, some from France, under a scheme operated by the New Zealand government. Most were farm-workers or domestic servants, with a scattering of skilled tradesmen, joiners and gardeners, a cook, and a few policemen. Some of the emigrants had been 'nominated' by friends or relatives already in New Zealand, and among these were the Thomson family - going to join John's brother Charles who had emigrated earlier and a girl whose name is not known today but who, according to family belief, travelled with them and was going to marry Charles.

The Thomsons' story must have been typical. John Thomson was the eldest son of another John Thomson, meal miller in the village of Barr in the parish of Killean, where he and his wife Sarah, known as Mysie, appear in the census of 1851. (These ten-yearly snapshots of who lived where and with whom, as well as miscellaneous bits of other information, are a marvellous resource for the historically-minded, and are increasingly available on the internet.) In 1851, John and Mysie had a family of six boys - John, then aged 15, Neil, Hector, Charles, Duncan and Lachlan Dugald - and a girl named Ann. Young John's occupation is given as Assistant Miller, which at 15 must have given him some pride. With the exception of Ann, who was 13, all the other children arc listed as 'scholars', even three-year-old Lachlan Dugald. Meal mills were not goldmines, and their dwelling was modest, a small house with only two rooms that had windows, with large beds let into recesses in the thick stone walls as was customary in Highland cottages.

A few miles north of Barr, in the farm of Drumnamucklach, lived the Black family, the youngest of them 12-year-old Barbara, who was to marry John Thomson. There were seven windows in this house, and the family seemed more prosperous. Her father Lachlan was the farmer; her mother Effie Hamill (sometimes Hamilton) came from the village of Clachan in the neighbouring parish of Kilcalmonell. Effie's parents were weavers and she had grown up in the hills slightly north-east of Clachan where there was a generously-flowing burn, a necessity for their occupation. In the 1851 census Lachlan and Effie had six children living with them, from 28-year-old Gilbert, through Archibald, Betty, Donald, and Duncan down to Barbara. Only Duncan and Barbara are listed as scholars; the other boys worked on the farm and Betty appears as a 'housemaid', whether in her parents' house or elsewhere is not apparent. Ten years later the Black family had moved from Drumnamucklach across West Loch Tarbert to the 300-acre farm of Keppoch in Kilberry. There is no mention in this census of Betty - perhaps she had died - but all the rest were there and working on the farm. Meanwhile the Thomsons were still living in Barr, where father John, now 70, is described as 'Wright and miller', young John as 'wright' (we would say joiner) and Charles as apprentice wright. By now the meal mill and joinery were hardly providing enough of a living and as the children grew up some of them had turned to other trades; Neil was a lobster fisher, Ann a domestic servant, and Hector a farm-worker. Sixteen-year-old Duncan and Lachlan Dugald, 13, were still at school. It was in fact a time of economic uncertainty in Kintyre, as in many country places in Scotland. The farming 'improvements' of the previous hundred years had brought more effective methods, but a downside too: great landowners such as the Duke of Argyll were now inclined to see their property as a source of income from rents, and became less concerned than formerly with their role of patron. Often when the customary 19-year lease ran out, a farm would be joined up with neighbouring land and the rent increased, so that the previous tenant could no longer afford it. This meant bigger farms for some, but loss of livelihood for others. And it didn't help either farmers or meal millers that grain was increasingly being imported from the American prairies in steamships and sold more cheaply than the home-grown product. At the same time, the population was growing fast; the enumerator for Barr district noted that 90 families were living there in 1861, and families were large. By 1870 pauperism was common.

More and more people were looking elsewhere for a solution and emigration increased rapidly, to the extent that between the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and the outbreak of the First World War a century later, nearly two million people left Scotland for Canada, America or the Antipodes; and often the emigrants sent enthusiastic letters home describing how much better their lives were in the new country, and, perhaps most tellingly of all, how free of social classes and distinctions. Not everybody saw it like that. Emigration also brought heartache, especially for those left behind. And writing his parish report in the Statistical Account of Scotland, the Rev MacDonald, minister in Killean and Kilkenzie, deplored the exodus and declared his conviction that not one of the emigrants 'would relinquish their hills and glens, to which they are attached by the dearest of ties, could any reasonable prospect of employment and support be held out to them in their native land'.

Perhaps it was lack of work that drove John Thomson to leave Barr and go to Glasgow, or he may have already had it in mind to emigrate and thought he could save money towards that ambition more easily in a city. At any rate, in 1866 John Thomson and Barbara Black were married in the parish of Govan. Barbara's father Lachlan Black had died the year before, and during the 1860s her brother Archibald moved to Dalkeith Farm, back in the parish of Killean; changes were afoot for both families. Others of the Black sons moved to separate farms, and of the Thomsons, by 1871, only Neil was still in Barr village, married now with a family and working as a fisherman. The father John died in 1872.

Young John and Barbara's four children were all born in Govan, and it may have been from there rather than Killean that they set out for New Zealand. But mystery surrounds the girl who went with them to marry Charles.

The Cospatrick passenger list shows only seven 'Colonial Nominated Emigrants' who came from Argyll, the six Thomsons and seventeen-year-old Emily Doughton. The assumption must be that it was Charles who nominated them. But who was Emily? She doesn't show up in any birth records for Scotland, and Doughton is not a Kintyre name. Quite possibly she came to Argyll as a servant in one of the big houses in the district, and so met Charles; it was normal practice for the owners of such houses to have a residence in London, and move servants around between the two. Other single women on the ship included Margaret McQueen, aged 21, and Margaret and Jane Scarff, 19 and 16 respectively, who all came from Lanark. Could one of them have been in Govan and met Charles when he visited John and Barbara? It is possible, but seems much less likely as none of these was a 'colonial nominated emigrant'.

At all events, the little group from Argyll must have been full of excitement, no doubt laced with sorrow at the parting, especially from the widowed mothers, as they followed their star of hope and set out on the great adventure. And for them, as for all the emigrants, it must have taken no little courage to face first a long sea-voyage in cramped accommodation, and then the challenge of an unknown country.

For two months all went according to plan, with the ship making fine progress and her passengers getting their sea-legs. The Cospatrick was flush-decked forward of the main mast and would have been a good sailor, fast and weatherly, though perhaps inclined to be wet in a strong wind because of spray flinging across her deck. No doubt this was great fun for the many children on board, and it is easy to imagine their games and their laughter, and the friendships springing up between young people who shared such mixed feelings of sorrow and exhilaration.

And then, when they were 600 miles south-west of the Cape and alone in a huge ocean, on a windy night and with a fast-running sea, suddenly disaster struck. At midnight on November 17 the second mate, Henry MacDonald of Aberdeen, finished his four-hour watch and went to bed. Half-an-hour later he was roused by loud shouts of 'Fire!' and scrambled back on deck to find smoke pouring from the fore hatch, and panic-stricken passengers, wakened by the noise, crowding up to the deck. Amid the consternation, Captain Elmslie, trying desperately to contain the fire, ordered the ship to be put before the wind, but in spite of enormous efforts it could not be done. Within a quarter of an hour, flames burst out of the fore hatch and then the ship came suddenly full head to wind, spreading the flames aft with heavy choking smoke and setting fire to many of the lifeboats. MacDonald and others of the crew asked the Captain to lower the remaining boats, but he was still intent on saving his ship; however, the panic was by now extreme and frantic passengers with screaming children hampered the efforts of the crew. Then, in the terrifying pandemonium, many passengers rushed the quarter boats hanging from davits over the side. About 80 of them crowded into the starboard boat; the davits gave way under their weight and her stern hit the water, capsizing her and throwing everybody in her into the water. Within a few minutes they all drowned.

By now flames had raced the length of the deck. Then in quick succession the fore, main and mizzen masts crashed down. There could no longer be any hope or saving the ship, and the Captain gave the order for each to save himself. The crew managed to lower the port quarter boat, with 33 people inside, and when she reached the water MacDonald, a woman passenger and the first mate jumped down into her; moments later the ship's stern blew out with an enormous roar. Survivors in the quarter boat watched as the Captain threw his wife over the side and then followed her, while the ship's doctor picked up their little son in his arms and leaped after them; they, too, all drowned. It was not quite a quarter to two.

For the rest of the night the port boat stood off at a little distance from the burning ship, and when daylight came the starboard boat, which had somehow been righted and was full of emigrants, appeared nearby. She had no seamen aboard, so MacDonald and a few others joined her while the first mate, Mr. Romaine, remained in charge or the other boat. Both stayed with the Cospatrick until she sank on the afternoon of the 19th, when they abandoned the scene and set course for the Cape.

For two days they managed to keep together. Until now 63 people had survived, with 23 passengers and nine crew in MacDonald's boat, and six crewmen, 25 passengers and a tiny baby in Romaine's. But neither boat had food or water, and they had only the most makeshift of masts or sails; an Irish girl gave MacDonald her petticoat to improvise a sail. Then the wind rose further and during the following night the boats became separated, despite whistling and shouting to keep in touch.

As days dragged past and the sun bore down on them their plight became increasingly desperate. MacDonald told later how some, driven by hunger and thirst, drank seawater and went mad; one by one they were dying, and eventually those who were left resorted to eating the livers and drinking the blood of the dead before putting their bodies overboard.

And then, at last, 10 days after the fire started and more than 500 miles north from where it happened, MacDonald's boat was sighted by the ship British Sceptre, and the five men in her who were still living were rescued. It was almost too late. Though Captain Jahnke and his crew treated them with the greatest care and kindness, two of them, a passenger and a crewman, died soon afterwards; only MacDonald, the quartermaster Thomas Lewis and an 18-year-old seaman named Edward Cotter reached St Helena, where on December 6 Captain Jahnke put them ashore to receive proper medical help. When they had recovered a little, the three men were taken on board the mail-steamer Nyanza, bound for Plymouth, and were finally on their way home.

In spite of an extensive search by the Royal Navy, Mr. Romaine's boat was never found, and not one of the Cospatrick's emigrants survived.

At home, it was a bleak turn of the year as news of the tragedy filtered through. The Governer of St Helena sent a despatch to the Secretary for the Colonies on December 10, and the Nyanza called at Madeira where a telegraph was sent to London on the 26th; she reached Plymouth at the end of the month. By New Year 1875, the story was in the newspapers, including the Campbeltown Courier which in a grieving paragraph on January 2nd gave the names of the six Thomsons 'from Glenbarr, in this district'. Then interviews with the survivors brought out the harrowing sequence of events. The Daily Telegraph (Cospatrick article.) carried a most graphic account, taken up by papers all over Britain, including the Oban Times, in which the story filled an entire column of its single sheet of January 9. And the Illustrated London News gave it prominence for three weekly issues, with pictures of the ship, her Captain and his family as well as the survivors. It seems the whole country was in shock; simple people at home and in New Zealand, like the Thomsons and the Blacks, mourned their shattering loss. And as for poor Charles Thomson, waiting to greet his family and bride, does anybody out there know what became of him?

An inquest was held by the Receiver of Wrecks for the Port of London, and the three survivors gave their evidence. Apparently the fire started in the boatswain's locker, in the forward part of the ship, which held large amounts of inflammable materials including ropes, tar, cotton waste, oil and paint.

The Thomson stone in Killean churchyard was erected in March 1876, a little more than a year later, and, unusually for the time, it does not record who erected it; perhaps it was the heart-broken Mysie. She died herself on November 20, 1878, four years almost to the day after the disaster. Effie Black died in 1879 at Dalkeith, where her son Donald was now the farmer; after losing his wife in 1876, Archibald had moved with his family of five sons and a daughter to the farm of Barr Mains nearby, and he married again four years later.

Neil Thomson and his brothers Hector and Lachlan Dugald remained in the district, and Lachlan Dugald married my grandfather's sister Catherine MacDougall. In succeeding generations many of the Black family emigrated to Rhodesia, in steamships rather than sailing vessels; and there are descendants of both Thomsons and Blacks still living in Kintyre.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to Denise and Peter for the Cospatrick's passenger list; Norman Newton, Senior Librarian and Information Co-ordinator, Highland Libraries; Murdo MacDonald, Archivist for Argyll and Bute; Alison Ferguson, Registrar for Inverness; and to Angus Martin, Les Horn, Ian and Ina MacDonald, Elizabeth Marrison and Frances Hood. I am grateful to them all for their help and advice. Denise and Peter's website is http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ourstuff/Cospatrick.htm

/p>

JAMES MCNEILL WHISTLER. Apropos Margaret Macaulay's item (previous issue, p 34), Mr. John Martin, Gigha, reports that, concerning the American painter's antecedents, some 15 years ago a party from North Carolina visited Gigha on the understanding that Whistler's great-grandfather, William McNeill, had originated there. Mr. William C Fields, a reader in Fayetteville, North Carolina, has, however, written to say that William McNeill's place of origin has not been established, though it is known that his wife, Elizabeth, was a daughter of Daniel (Donald) McNeill of Taynish in Knapdale, who, along with ColI McAlester and several others, was a leader of the 1739 Argyll Colony. 'It is possible,' he concludes, 'that William came with that group as a young lad, but he may have come later; we simply don't know.' Editor.

Graeme Reynolds

Margaret Williams also held 20 shares in the Exhibition No. 1 QMC at Maldon, a distant mining town, from 12 July 1884. This company paid dividends in October 1884 and May 1885. The rapid increase in the price of the payment, doubling, from May 1884, suggests that this was a prosperous venture. For a 10s share, Margaret received dividends of £1 2s and £1 5s 9d per share. The dividend implied that the market price of the share was considerably more than the face value.

Margaret Williams died at Deep Lead, Victoria, on 24 May, 1886, aged 37 years. She left a family of 10 surviving children, two sons having died as infants. Some glimpse of the death has been located in a letter from Herbert Williams's brother at Odessa on the Black Sea. This brother, Robert, a merchant sailor, wrote in May 1887 that he had received a letter from home - probably meaning Tytlen, Caernarvonshire - that Herbert's 'dear wife had departed this life and leaving you all orphans'. Robert continued to narrate that 'Margaret [assumed to be his own wife] said in her letter that her heart was saddened because of you all and that she has wept bitterly during the night in her bed thinking of you esp[ecially] the children'. Robert remarked that the delay in writing was attributable to another brother, William, who had not told him of the death. Robert and William Williams, mariners, had visited Margaret and Herbert Williams at Deep Lead in the early 1880s. Robert's letter contained three pages of phonetic English and a fourth page of similar Welsh. From this mix of language, Robert provided another insight into the family. He continued: 'I'll send word to you again, and I see the way clear I'll keep my promise to Ellen and [Isa]Bella. Now I'm hoping the children are doing all right and caring for the little ones and that you and Andrew are having ... or ... paying better than ...'

The omitted words are illegible. The meaning is unmistakably a reference to the success of Herbert and Andrew, the second surviving son, in mining.

The early demise of Margaret Williams and her widowed husband's later marriage in 1890 to Susannah Prydderch, a colonial-born woman of Welsh parentage, would appear to have contributed to the fragmented nature of any information about the Williams children's maternal relatives. Susannah's parents lived nearby. Her father, Jonathan, was a leading shareholder in the Crushing Company. It also placed heavy responsibility on the elder daughters. Initially, Ellen, who died in 1893, and Isabella managed the home and reared the younger siblings. Jane, born in 1879, would later recall 'working at home' from the age of about six years. Any domestic relief from the introduction of a step-mother, Susannah, was barely transitory. Susannah died in childbirth within the year, leaving the daughters to resume supervision of the running of the household and to rear a baby. This baby moved to the Prydderch family, who raised him. That Ellen and Isabella would rear their younger siblings in a period of diminishing prosperity for gold mining and through a major economic depression of the 1890s with only the support of the Prydderch family, has been taken as reasonable evidence that none of Margaret Ballantine's closer relatives were in Victoria or nearby at the time. There is no memory of these people being asked to assist the family or of any of the younger children having been sent to reside with relatives. Ellen and Isabella supported their father to keep all the children together.

Deep Lead remained a cosmopolitan settlement. Welsh and German surnames were common among the English forms. Chinese were in sufficient number for the Williams children to have a smattering of Chinese greetings to be applied to Mow Fung, licensee of the hotel. There is little to suggest that any of the children could read the Welsh of their father's letters or his Bible.

The Williams family's oral traditions have focused on the Welsh influences from the paternal line and have preserved little of Margaret's background. Despite this failure of oral records, the names of her 12 children - Herbert, Thomas Herbert, Hugh Robert, Ellen, Isabella, Andrew, Margaret, Robert, Jane Elizabeth, Janet, Herbert, Annie Ballantyne - conform to an accepted Scots pattern. The Scots and Welsh names were inserted in the appropriate positions. Perhaps the innovative features of this pattern are the transformation of the surname, Andrew, to a forename and the addition of second names.

In this family, the names of Jane, Jean and Janet have been used frequently. This usage, the loose spelling and some interchange of the names add some complexity to the discovery of this family. One feature of the family's oral tradition has been that 'Janet' was articulated as 'Jenet', rather than as 'Janet' with the long vowel of the Australian accent. This also maintained Jane as a distinct name.

Margaret Williams lies buried at Deep Lead. The grave is known only by its low hewn rock border and its location adjacent to Susannah Prydderch's parents' grave. There is a family account that when Herbert Williams died in 1921, the wives' coffins were relocated so that Herbert's could be laid between them with all burials placed at the same depth. This placement appears to have been complex, but it probably reflects the children's desire that the wives be afforded status with Herbert. Herbert Williams had been a member of the Cemetery Trust. He was also widely known in the district as 'Daddy Williams', a name applied by people of all ages and even young children as the formal means of addressing him.

Fossicking for alluvial gold not only persisted in the outer fields at Stawell but also accommodated the perpetuation of the independent digger, who would 'partially starve' fossicking rather than abandon it for a labour-system of employment. Deep Lead's geology and small populace, post-1880, replicated this independence.

Herbert and Margaret Williams paved a careful, middle path. Frugality kept them in modest comfort. To the end of his days, Herbert handled declining amounts of money and was able to preserve a simple lifestyle by the standards of his contemporaries.

Catherine Brown

The eldest daughter, Catherine, married John Ralston of Brecklate, Southend, in December 1834. From the return in the 1851 Census, Brecklate, a farm of 130 acres where four labourers were employed, was the residence of John and Catherine Ralston and nine children. The nine children included the elder siblings, Catherine, Agnes, Thomas and James. The presence of a younger sibling, Catherine, in 1865, suggests that the eldest daughter died after this Census.

A surviving letter written by John Ralston in November 1849 to his 'brothers' in Winnebago County, Illinois, USA, referred in part to George Picken, Andrew Giffen and John Picken in that area, in addition to Alexander, John and Jean Ralston, assumed to be more distant relatives in the USA.

It is possible that the first of John and Catherine's children to emigrate to Victoria, Australia, was Thomas, who was baptised in 1837. A Thomas Ralston, 28 year old passenger per the Beechworth sailing from Liverpool on 24 December, 1858, disembarked at Geelong, Victoria, shortly before the voyage was completed at Melbourne on 11 April 1859. The passengers had last sighted land on 5 January. Some view of the expected duration of a voyage might be gleaned from the report that this voyage of 108 days had experienced light winds and had been becalmed for 25 days. Connecting the son Thomas with the sailing detail is tenuous. The cited age is about seven years more than would be presumed from the baptism. The detail may also refer to Thomas, son of Alexander Ralston and Elizabeth Ferguson, a cousin. In any case, the elder son settled in Victoria.

It is possible that another son, James Ralston, was the 22 year old migrant per Prince Consort, which left England on 14 March, 1861, and arrived at Melbourne on 30 June. This voyage had crossed the Equator on the fortieth day from England. After sailing in fine weather to near the 'parallel of St Paul', the ship later entered five days of gales and 'head winds on the [Australian] coast'. This reference to St Paul may have been ambiguous. St Paul's Rock at latitude 1° N and 23° W, near the Equator in the Atlantic Ocean, as well as Isle de St Paul at 38° 44' S 77° 30' E in the Indian Ocean, could both have been on the course. Since the former is in such a low latitude, it is more likely that the equatorial location is more applicable.

The age recorded for James is remarkably close to the baptismal date for the son at Southend. At least one and perhaps both voyages may have paved the way for the migration of six siblings after the death of the widowed Catherine Ralston in March 1864. This major emigration meant that all but two of the 10 children in this family emigrated. John Ralston, aged 20, and his younger siblings, Mathew (18), Isabella (16), Marg[are]t (14), Ellen (12) and Catherine (10), who were all described as 'English', sailed as unassisted passengers on the Black Ball Line's 1,266 ton ship, Southern Ocean, from Liverpool on 8 November, 1864. Probably the term 'English' was used to show that they were not Gaelic-speaking Highlanders. This voyage weathered 12 days of gales in the Bay of Biscay followed by 'very light trade winds'. In the southward direction 'while doing her easting, in latitude 45° South', the trip was driven by 'strong favourable winds'. Upon arrival in the waters of Victoria, the ship was placed in quarantine and brought to Hobson's Bay late on Saturday evening for the examination by the Immigration Officer on the following day. All passengers were declared healthy and the trip ended on 18 February, 1865. There were 11 cabin and 372 other passengers on this vessel. It is possible that the Confederate warship Shenandoah, shortly out of Melbourne, had passed the Southern Ocean in the waters before Melbourne.

Mathew Ralston returned to Scotland, married and later settled in Illinois, USA. His travels suggest that for a time the familial links between the Ralstons in Victoria and Illinois were well-established. His siblings had become established in the Bungaree district, east of Ballarat, by at least the 1870s.

Apart from the location there is no additional evidence to suggest that the Patersons and Williams' were in contact with the Ralstons in Victoria. However, for such closely related people to travel to the one region without knowledge of the other or without having some later contact with one another would be inconsistent with the patterns established by the families of the previous decades in America. On arrival, they stayed with close relatives or close friends before moving to make their own homes. Despite that practice, the families in Australia made their own ways in a new colony.

Acknowledgements

The information on which this work is based has been gratefully enhanced by contributions from Bronwyn Millis, Anntoinette Ralston, Grace Ralston and Elizabeth Johnston. Additional detail comes from the Southend OPR 532, the Public Record Office of Victoria and The Argus [Melbourne].