THE KINTYRE

ANTIQUARIAN and

NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY

MAGAZINE

Issue Number 68 Autumn 2010

CONTENTS

- Campbell Mitchell, RSA; Murdo MacDonald p2

- Campbell Mitchell, RSA; J Shaw Simpson p4

- Editorial Notes; Angus Martin

- Hamish MacKinven and Donald Kelly p7

- James Caw Senior; Angus Martin p8

- MacKean Stewart: An Appreciation; George J Stewart p 11

- Singing Songs of the Scottish Heart; Angus Martin p14

- Fresh Light on Robert Bums's Highland Mary; Gerard Carruthers p16

- By Hill and Shore; Angus Martin p 18

- Botanical Report 2010; Agnes Stewart p26

- Otter-Watching in Kintyre ;Christine Russell p27

- An Otter Encounter; James MacDonald p30

- Butterfly Reports ; S Walker & I Teesdale p31

- Kilkivan Chapel Collapse; Angus Martin p32

- The Dalton Plan ; Murdo MacDonald p33

- Tragedies Close By; Argyllshire Herald p34

Murdo MacDonald

The year 2011 will mark 150 years since the birth of J Campbell Mitchell, RSA, one of the trio of distinguished artists born in Campbeltown in the nineteenth century. He is, of course, completely overshadowed by William McTaggart, as any Scottish artist would be. He never gained the honours or status of Sir George Pirie. Nevertheless, his work is described and illustrated in studies of Scottish art, such as Sir James L Caw's Scottish Painting Past and Present (1908), or, more recently, Professor Duncan MacMillan's Scottish Art in the 20th Century (1994).

John Mitchell (later Campbell Mitchell) was born in Shore Street, Campbeltown, on 1 December 1861, the second child of John Mitchell, grocer there, and his wife Janet MacMillan. John and Janet had been married on 20 October 1858. Three other children were born to them: Martha, on 15 October 1859, Jessie Mary, on 1 January 1865, and James Hamilton, on 6 August 1878. Jessie, however, died in infancy.

The later appearance of 'Campbell' in the artist's name remains unexplained - it was not a family name. (There is a curious analogy here with another artist son of Argyll and Bute: G Leslie Hunter, the Scottish Colourist, born in Rothesay in 1877, was simply registered as George Hunter.)

Census records indicate that John Sm. was a native of the village of Lochgi1phead, the son of John Mitchell, tailor there, and while his stated age would indicate a birth date of c. 1834, no record of his birth has been found yet. But Pigot's Directory of 1837 does indeed list John Mitchell, Lochnell Street, a tailor in what was then the new and rapidly growing village of Lochgilphead.

Janet McMillan, born in Campbeltown in 1836, was the daughter of Malcolm MacMillan, ship carpenter, and Martha Galbraith. Malcolm was the proprietor of a tenement in Shore Street, including the Steamboat Inn, and it would have been in the house owned by his maternal grandfather that the artist was born.

At the time of his marriage in 1858, John Mitchell Sm. is designated as a steward. In the birth entries of his first two children he is stated to be a grocer. He went on to prosper as a wine and spirit merchant in the 1860s and '70s, acquiring premises in Longrow, Burnside and Cross Street, including the Commercial Inn. In a large advertisement in the local newspapers on 15 July 1871, he intimated to the public that he had 'opened his new premises in Longrow with a large and carefully selected stock of Wines, British and Foreign Spirits, Malt Liquors, etc., which he intends to sell at prices strictly moderate'. His following list of prices includes items such as brandy and champagne at 60s per dozen.

The young J Campbell Mitchell attended Campbeltown Grammar School. As his name is not recorded in the school's Register of Admissions, which begins in August 1873, we have to assume that he had already left. He was employed initially in the office of Messrs. C & D Mactaggart, the old-established law firm. His heart was not in legal work, however, but according to the obituary in the 95th Annual Report of the Council of the Royal Scottish Academy (Royal Scottish Academy Archives), it was not until 1884 that he was able to begin formal training in art when he enrolled at the Trustees' School of Design, Edinburgh. In 1887 he trained briefly in Paris under Benjamin Constant.

From 1884, therefore, the artist was based in Edinburgh, settling finally in 1903 in Corstorphine, where he lived until his death on 15 February 1922. A visit to Galloway in 1891 captivated him and he came to be associated with the sweeping moors, hills and cloudscapes of that region. Even so, Kintyre subjects continued to feature in his work throughout his career, such as 'On the Kintyre Hills', now in the Burnet Building, Campbeltown, but first exhibited at the RSA annual exhibition in 1905. His RSA Diploma Work, deposited in 1919, was 'The Waterfoot, Carradale'. (Collection of the Royal Scottish Academy)

Both the Campbeltown Courier and the Argyllshire Herald kept an eye on 'our townsman' and regularly reported on Mitchell's career with great pride. From 1908, the artist was a member of the Kintyre Club. Like all the members of his family - father, mother, sister, brother - he held shares in the Campbeltown & Glasgow Steam Packet Joint Stock Co. Ltd. Reminiscing, in an article in the Campbeltown Courier of 23 September 1922, about Archibald MacKinnon's short-lived Kintyre Art Club of 1886/87, the Rev Dr A Wylie Blue, Belfast, recalled that both Mactaggart and Mitchell 'smiled goodwill on our modest Club and gave it a helping hand. Mr Mitchell not only sent pictures occasionally but came in person, when he happened to be in town, to listen to our criticism of them' .

John Mitchell Sm. gave up his business c. 1889 and retired with his family to Edinburgh. He took up residence eventually at 151 Bruntsfield Place. This is a high white sandstone comer tenement of four stories and mansard roof. At the time this was a new expansion of the city into the Marchmont/Bruntsfield area on the South side, and the Mitchell family were probably the first occupants of the flat. John Sm. died there on 12 February 1896, a man of 'bright and genial disposition', according to his obituary in the Campbeltown Courier, 15 February 1896. His body was brought back to Campbeltown to be interred in Kilkerran burial ground. A gravestone close to the entrance gate commemorates John Mitchell, his wife Janet MacMillan, who died on 14th November 1920, and their infant daughter Jessie Mary. Acknowledgement: Nicola Ireland, Assistant Curator, Royal Scottish Academy.

by J. Shaw Simpson

Among Scottish landscapists, the subject of our article [published in 1921], Mr Campbell Mitchell, has achieved considerable renown. Born, like McTaggart, in the seaport town of Campbeltown, he received his early scholastic education at the Grammar School there. What the boy is to become is the unending parental quandary - and that quandary must be extremely difficult where the lad betrays no specific bias or inclination. Mr Campbell Mitchell's father temporarily solved the matter by sending his son to occupy a legal stool. It inoculated him with some ideas of business and order and method - to that extent serving quite an invaluable function: but the youth whose pencil insists upon drawing boats, or sketching, quite good naturedly, the features of clients, is clearly out of harmony with the frigidity of the law. A legal office was preposterous. Even as a lad, he used to lie on the floor with his drawing material, his eyes riveted upon some objects: and at school he entered into an agreeable quid pro quo with another lad whereby if he, the other lad, would do his 'sums', he, the incipient artist, would cover his slate with sketches.

'The Youth, who daily farther from the east

Must travel, still is Nature's Priest,

And by his vision splendid

Is on his way attended.'

The father was obliged to reconsider his son's future: and, like a wise man, he deferred to the son. An interview with McTaggart ensued. The father submitted the son's drawings. McTaggart gave his judgement without reserve. 'There may be,' he said, 'a great artist in his skin: but he will have to work for about twelve or fifteen years before he discovers it.' A declaration of this nature would have abashed a timid, faltering, hesitating youth. Young Mitchell accepted it with equanimity. Is there anything to equal the perfect loyalty of youth to its ideals?

The next few years of the future artist's life were devoted to study in Edinburgh under Mr Hodder, and before entering the life class, he proceeded to Paris to study under Benjamin Constant - a rather unusual proceeding. Alike as artist, teacher, and man, Constant was an inspiring personality. The youth, who had not seen a picture exhibition until his twentieth birthday, was naturally obsessed with Paris, its environs, the Seine, etc. Street, square, river, atmosphere, and people, and above all Constant - what an artistic, beautiful, and synthetic unity! The impact was too tremendous at the moment to be aesthetically analysed or understood, but the hour and its tremendous beauty still retain a tincture of their original captivation.

Returning to Edinburgh, he entered upon his studies at the life class with an agreeably widened and enlarged outlook. Thither came Lawton Wingate, Robert Alexander, Robert McGregor, Darling McKay, and W. B. Hole: the future grand old men of Scottish art, and, with the exception of Hole, still predominant in their respective spheres. With another student he divided the Keith prize for the best work exhibited. He had now acquired what the schools can legitimately confer upon the student. He had painted in the open air repeatedly during his pupilage: but now the acute loneliness of his position disturbed him. The disturbance, however, was momentary. He never doubted the existence of the artist 'within his skin'.

In 1885 his first small work, 'Near Carradale', was sent to the R.S.A. A background of trees and sky, and in the foreground a stream of clear pearly water. To what may it be compared? The faltering steps of a child. The child fears to 'lippen', though its strength is greater than its confidence. 'Near Carradale' would restore the faith of the dejected. I do not know if many artists retain their original exhibit. It would be an excellent thing to have beside them, just to look at now and again: to indicate how far they have travelled: to denote the nature of their progressive development!

There are probably few communities in which art as a pursuit is so poorly esteemed as Campbeltown. Her gifted sons honour the town, the town betrays no great anxiety to honour them. This general indifference apart, the town itself is admirably situated to promote the artistic faculty. There is the vast empyrean, which Mr Campbell Mitchell as a boy learned to love: there are the vagrant clouds which the winds perpetually beleaguer and scatter: while, at Machrihanish, the resplendent, tumultuous blue waves crash upon the shore. Other influences, however, were requisite, and these the county of Galloway supplied. Always loving the sea, he also formed an affection for the· Galloway moors. Those moors had a glamour, an orchestration of colour, which he reverently aspired to reproduce. The sea's eternal surge is apt to subdue or overwhelm the individual: but the moors had a certain tense appealing romanticism. Galloway thus completed his art education. It is not enough for the artist to be the product of the schools, however diligent the desire of the schools to educate him. Nature is the mistress with whom he must live. He has sworn unalterable affection, and fealty to her must be impeccable.

Close communion with Nature is the joy of Mr Campbell Mitchell's life, and the secret of his success. He has not sought to evade her eternal appeal. He has opened his heart and his imagination to her mystic ministry: and the measure of his success is in exact proportion to the extent of his devotion to her. In his depiction, however, certain reservations require to be noted. The artist concerns himself very little with the topography of the place. He is more interested in movement and Nature's mood at the given moment. He observes detail without necessarily recording it. What he gives us, therefore, is a rescript of his own vision instead of a multiplicity of engrossing facts. Furthermore, the . artist studiously subordinates himself. He has no desire to impress the spectator with his own personality. In an exhibition you may frequently hear the exclamation: 'Oh, that is by so-and-so', and it is by 'so-and-so'. The personality, or shall we say the manner, of 'so-and-so', is as conspicuous as sunlight. The personality of Mr Campbell Mitchell is in his work too, but it is minimised, if not eliminated, in deference to the exceeding beauty of the thing to be represented. An idea of this beauty, to those who are ignorant of his work, may be gleaned from our reproductions. 'The Plains of Lora' was purchased by Dr John Kirkhope, and is now the property of his trustees. 'Knockbrex Moor' carries us back to the Galloway the artist so ardently admires. 'Moonrise, Findhorn' is the property of Mr Douglas Oliver of Hawick. The landscapes are delectable. If we hadn't known of the painter's devotion to Nature those two pictures would have imparted the requisite knowledge. The cloud masses and the graphic configuration of the earth could only have been depicted by an artist in vital communion with the objects represented. 'Moonrise', on the other hand, envisages his early and prolonged affection for the sea. The poetry of Nature, which a few are unable to detect in much of his other work, invests this picture with an almost indescribable charm. As a composition, it is an unqualified success, while as beauty it moves us with a passion akin to music.

Mr Campbell Mitchell's work is now distributed throughout the galleries of the world. His 'Argyllshire Moorland' is in Munich: 'On the Kintyre Coast' in Wellington, New Zealand: 'Spring in Midlothian' in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool: 'Aberlady' in the Art Gallery, Aberdeen: and 'The Haunt of the Curlew' in the Smith Institute, Stirling. At the present exhibition of the R.S.A. he has three canvases the sight of which would alone repay the cost of admission.

Through rigid adherence, therefore, to his ideals, and persistent devotion to study, both within doors and without - the latter especially the little lad whose dreams of beauty and Nature filled his soul with unconquerable longings is now one of our eminent Scottish landscape painters. Before the period prognosticated by McTaggart had elapsed, the artist that was 'within his skin' had quietly and victoriously emerged. The youth on the legal stool who nourished his secret ambitions with surreptitious sketches has almost imperceptibly merged into the region of spectral mist.

by Angus Martin

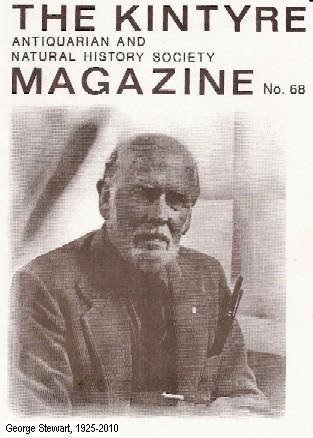

An Appreciation by George John Stewart of Dalbuie

My father was born in 1925, the first son of George Stewart, a stonemason and builder from Blantyre (and subsequently Bothwell, in Lanarkshire) and Eileen Atkinson from Northern Ireland. He was the fourth in line to be named George, and the only one in the family I know of to be given the name Prince. I suspect that this was a fanciful name that my grandmother gave him as her firstborn - and an appropriate name too, when one sees the young George in the earliest photographs of him. My grandmother thought the world of him, not only naming him 'Prince', but extracting the promise from my grandfather that, although he would be christened with the 'family name' of George - a name she disliked - she should be allowed to call him a name of her choosing. She chose the name 'Tony', and Dad was known as such to most friends and acquaintances all his life. His other middle name, McKean, reveals something of our family history - it was passed down in the family that we were descended from the Stewarts of Appin, in Lorn, and McKean is a rendering of Mac lain. The designation of the chief of the clan is MacIain Stiubhairt na h-Apainn~ or merely MacIain. Dad recalled his grandmother talking proudly of the connection, although she herself was a Campbell. The family were most likely among the many from the Highlands who flooded to the great metropolis of Glasgow to find work sometime after 1745. When exactly is not known, although Dad tried for a number of years to find out. His grandfather became well known and respected for his building works, which included the City Chambers in Dundee and the Aluminium Works in Kinlochleven.

After Craigflower Preparatory School in Fife, Dad was sent to Glenalmond in Perthshire for his schooling. Not an entirely happy experience for him, as he missed being with the family, but he would speak well of the school and was proud of being an 'OG'. It was while at Glenalmond that my grandfather died of a brain tumour, and Dad's time there was cut short - it was deemed that the elder son should be at home to look after the family, although Dad's younger brother, Alan, was allowed to continue at CoIl. This was naturally enough a difficult time for the family, and, having just lost their father, my grandmother followed soon after - finding the stress of living without her beloved husband too much for her sensitive nature - leaving Dad, my uncle Alan and my Aunt Maureen in the charge of their aunt Arabella, known as 'Tib'.

Tib had married Robert Dunlop from Campbeltown, and through this connection many family holidays from the 1930s on were taken in Kintyre. Gartvaigh farm in Southend was a favourite, and some of Dad's earliest attempts at photography were of the farm and nearby Carskey. They were obviously very happy" times and, I believe, played a major part in our own family holidays' being Kintyre-focused, and of the eventual purchase of Dalbuie in 1971.

World War II saw Dad doing war service in the Fleet Air Ann, initially stationed near Brighton, where, in his free time, he went to Art Classes at the College of Art. His tutor there was the famed Scottish artist James McIntosh Patrick, then at the start of his illustrious career. Dad never lost his love and appreciation of McIntosh Patrick's work - in a style which deeply influenced his own.

Even from his earliest days, Dad had had a leaning towards drawing and painting, producing, at the age of 12 or thereabouts, a wonderful little 'nature diary', filled with notes and detail on birds, animals, plants and trees. Indeed, his love of natural things led to an interest in gardening. Dad created several gardens over his lifetime, and I would say that he was not just a gardener, more a 'plantsman', very knowledgeable on the conditions, soil, etc. that each plant preferred. And if you wanted to know what a particular flower was, he could often tell you the Latin name as well as the popular one. A couple of his created gardens were extensive and could have stood up against any of the popular 'visitor' gardens. His childhood notebook also contained many other things, including notes on architecture. It revealed an enquiring mind and set the pattern for Dad's interests for the rest of his life.

As a young officer, and stationed at Londonderry, he was present when 25 U-boats sailed in to surrender at the port at Lisahally, then the largest of the four bases covering the North-West Approaches.

After the war, Dad studied economics and statistics at Glasgow University, and, after graduating with an MA degree, joined the Burns Laird line as purser on the M.V. Laird's Isle plying between Glasgow and Belfast. It was there that he met my mother Jackie, who was ship's nurse. They married in 1952, by which time Dad had found employment at Alexander Dunn Ltd., a firm of fireplace manufacturers and heating engineers based in Uddingston, near Glasgow. The company was owned by the father of one of Dad's close friends, who knew of his drawing abilities, so Dad started as a draughtsman, and was part of the drive to create their unique under-floor warm air central heating system, eventually rising to the position of Managing Director when Alex Dunn Jnr. sold the company and emigrated to Melbourne, Australia.

After this Dad ran the company through many turbulent years and several changes of ownership, finally ending up as part of Lord Weinstock's GEC empire. His lordship wanted to close Airdun, as the company was known by then, and Dad fought for a considerable time through a difficult economic climate to keep the company operational and the men working. When Dad reached retirement, however, Lord Weinstock had his way, and the factory site is now a Tesco supermarket.

Retirement brought a permanent move to Campbeltown and a new career. Over his last few years at Airdun, Dad had returned to painting, at first in watercolour, but more and more in oils and acrylics, quickly establishing himself as a popular portrayer of Kintyre, and Argyll, in all its aspects. This new career lasted nearly as long as his earlier management one had, and it was a particular pleasure for me getting to know my father as a friend and fellow-artist as well as 'my Dad'. In 1989, when my wife Gill and I established The Oystercatcher Gallery in Campbeltown, Dad's work quickly became a mainstay of our artistic output. And before his failing health made such things too difficult to attempt, he was a regular and dutiful visitor to see 'what's new'.

At this time Dad also remarried, to Margaret Millar (originally from Kilkivan), and they remained together for some 30 years at Witchburn Terrace. He enjoyed his involvement with the many organisations he joined over the years - the Kintyre Antiquarians, for whose magazine he provided cover illustrations for a quarter of a century, the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and the Trades House of Glasgow among them.

To the end of his life, though born in Bothwell in industrial North Lanarkshire, Dad maintained a love of Kintyre and never ceased to want to describe that love in paint. The cruelty of his last year was that, for a man who had spent his life interested in the natural world in all its great diversity, he was confined to the house, and not very mobile even there. It was only a few weeks before his death that he came to realise that he might never lift a brush again, though he never stopped planning new pictures; and I would often be sent to the studio to get brushes or paint. He knew he did not have long to go, and faced that prospect with dignity.

I realise that in this brief chronology of a life, I have omitted so much about the man who was such an inspiration to me - his quirky sense of humour, his patience and gentleness, his helpfulness and sound advice, his constantly inquisitive outlook on life that kept his mind sharp to the end. And so much more. I only recall a single occasion when he lost his temper with me, and even then reluctantly: aged about seven, I painted all his tools and much of the inside of our garage in sky-blue gloss paint. It must have been a severe provocation on my part. But I also know how much that exercise in discipline cost him. He was always a gentle man ... and a gentleman.

There was a brief time in our relationship when I saw little of him. I was a young man trying to make my way in the world, with some success, and a good deal of failure (some of it conspicuous), but I was never condemned or berated, whatever Dad must have felt about it. He took being a father seriously, and of all his many talents, it is perhaps the one at which he excelled the most. Alongside me, my sister Ann and my brother Rory can testify to that.

1857. FATAL ACCIDENT. On Monday last week, as a

young girl named Catherine Norris, daughter of David

Norris, shepherd, Glenhervie, and servant with

Alexander McFarlane, farmer, Polliwilline, was herding

cattle along the shore, she discovered a lamb fixed in

the cliff of a rock, and whilst engaged in extricating

the lamb, she lost her balance, and falling over the

rock, was killed on the spot.

Argyllshire Herald, 28/8/1857.

1878. FATAL FALL DOWN A PRECIPICE. The body of James

Lees, lately shepherd at Glenharvie, Southend, was

found on Wednesday morning lying at the base of a

precipice called the Dune, near the shore, on the farm

of Glenharvie, Southend. Deceased was amissing since

Tuesday afternoon, and as fears were entertained for

his safety, a search was made along the shore in hope

of falling in with some trace of him. The precipice

down which he fell is not far short of 100 feet in

height. Deceased was married, and leaves a wife and

family.

Argyllshire Herald, 27/4/1878.

Copyright belongs to the authors unless otherwise stated.

It organises monthly lectures in Campbeltown - from October to April, annually - and has published its journal, 'The Kintyre Magazine', twice a year since 1977, in addition to a range of books on diverse subjects relating to Kintyre.

CLICK HERE for Correspondence and Subscription Information.

ISSN 0140 0762