Issue Number 78 Autumn 2015

CONTENTS

- Honour Restored for Great War Fallen: Tom Rowley

- Private Lachlan MacKinnon: Angus Martin

- A Sailor's Memoir, 1940-1941: Part I: Edward Duckworth

- Miles MacKinnon and a Hebridean; Emigration from Campbeltown: David Hutchison

- Tuberculosis in Kintyre, 1855-1930: Sandy McMillan

- The Charm of Gigha: George Blake

- Miscellaneous:

- 'In Lone Sublimity': Ailsa Craig: Murdo MacDonald

- The Ailsa Wink: Eric Dudley

- Botany and Butterflies: Agnes Stewart

- Book Review: Elizabeth McTaggart

- By Hill and Shore: The Sailor's Grave: Angus Martin

- Children in Court:

Tom Rowley

Somme Field

As the surrounding towns and villages have grown over the last century, open fields have slowly been overtaken with houses. Which is how eight soldiers from the 78th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force found their resting place in Fabien Demeusere's back garden in the hamlet of Hallu, 37 miles west of Amiens.

One rainy day in 2006, Mr Demeusere, then 14, noticed something unusual in the garden and went out to investigate. There he found a handful of bullets, which the heavy rain had brought to the surface. Intrigued, he grabbed a shovel and began digging. Within minutes, he had unearthed human bones, undisturbed for nine decades.

'It was a strange feeling,' said Mr Demeusere, whose parents had told him about the war and who had started studying it at week-ends. 'I felt something in my heart.'

Last week, he stood over a trench once again. Now 24 and an officer in the gendarmerie, he had put on his smartest suit and tie to lay a wreath as eight coffins bearing the remains he discovered were lowered into place at Caix British Cemetery, just a short drive away.

After Last Post was played, he knelt to place the flowers above the grave, then bowed his head.

In the coffins beneath him, two British-born soldiers, Private Lachlan McKinnon and Private Sidney Halliday, three Canadian comrades and three others whose bones remain unidentified were finally laid to rest with the honour denied them for nearly a century.

Behind the coffins, a dozen workmen in their Commonwealth War Graves Commission uniforms stood silently throughout the service, paying their respects to the men whose graves they would shortly plant with roses and mark with the same headstones as those of their 365 comrades already buried there. In front of them stood the oldest living descendants of Ptes McKinnon and Halliday, and the other men, the conclusion of almost a decade of historical, genealogical and scientific research.

'These men liberated my village and we owe them a debt of honour,' said Mr Demeusere after the service.

Lachlan McKinnon was born in Campbeltown on the Mull of Kintyre on November 15 1888. Three hundred miles away and seven years later, in October 1895, Julia Halliday gave birth to a son, Sidney, in Apple Tree Cottage in the Gloucestershire village of France Lynch. Her husband, George, earned his living making walking canes.

Both joined the thousands of Britons who moved to Canada in 1913. McKinnon became a butcher, while Halliday followed his brother, William, who had emigrated a year earlier, by working on a farm.

In December 1915, Sidney and William both signed up. William was refused on medical grounds but Sidney was accepted, as was McKinnon, who enlisted four months earlier. They must have been delighted that their war service first saw them return home to Britain, where, in 1916, McKinnon married his girlfriend, Christina.

Soon, though, they were packing up again, and dispatched with the battalion to France. In August 1918, they were ordered to retake Hallu, which had been captured by the Germans in March.

They took the hamlet on the 10th, but the next day they were driven back in three counter-attacks by the German Alpine Corps. In this battle for the village, both Halliday, 22, and McKinnon, 29, gave their final sacrifice, along with 44 of their comrades. The battalion's war diaries only recorded the names of officers who fell, but manila 'circumstances of death' forms were filled out for both soldiers, recorded as 'killed in action'.

McKinnon's form read: 'He and four of his comrades were killed by a shell that exploded in the trench they were in.' Halliday's form explained he was killed instantly by a shell explosion, adding: 'Owing to a temporary withdrawal from the position, his body could not be recovered for burial.'

Back in Britain, their parents learnt of the loss of their sons. There was not even a grave to visit, a focal point for their grief. When McKinnon's niece, Morag, died young, Lachlan's name was added to her gravestone in Campbeltown, in lieu of his own comer of a foreign field.

And there the story might have ended, had it not been for Fabien Demeusere's passion for history.

If he were not so fascinated by the Great War, he would probably not have kept digging, that day he found the bullets. He did not know then, of course, but one of the three sets of remains he uncovered was that of Sidney Halliday.

He immediately knew who to call: in a region where farmers are almost as used to turning up unexploded ordnance as their crops, and where the remains of two or three soldiers are unearthed each year, locals regularly have to summon staff from the War Graves Commission.

They swiftly identified the remains as Canadian because 78th Battalion badges were discovered with the bones. A few months later, as the Canadian authorities began archival research to establish which soldiers died in Hallu, the bones of five more soldiers, including McKinnon, were recovered from the Demeusere family's garden.

Historians concluded that the fallen of August II were the only Canadians to die in Hallu, which allowed them to draw up a list of 45 men whose remains the bones could be. In early 2007, four months into her new job, this list was passed to Laurel Clegg, a newly qualified forensic scientist.

She examined the bones to establish how tall the men were and their age, before cross-referencing these details with data recorded when the men enlisted. This shortened the possible list of men to 15.

That task was not easy, and took several years. 'A lot of them lied about their names and ages and where they came from when they moved to Canada,' said Ms Clegg. 'One of those we successfully identified wrote his name differently four times.'

This research led her to Jim Halliday, Sidney's nephew and William's son, now 72, who continued the family tradition by farming just a few miles from where his uncle worked the land in Manitoba.

But the matrilineal DNA test carried out on one of Jim's female relatives was inconclusive, and it looked like Mr Halliday might never know for sure whether these remains were his uncle's.

Then he remembered that his uncle had exchanged rings with his girlfriend, Lizzie Walmsley. Ms Clegg was astounded: near the bones they had found a locket with the inscription: 'L. Walmsley.' 'When I finally got that call that, yes, it was him and he had been identified, that topped it all off,' said Mr Halliday.

Ms Clegg also had trouble identifying McKinnon. Genealogical research indicated that his nephew, Thomas Bolton, had a daughter, but researchers failed to trace her. Two years ago, however, they came across a post by a Tom Haynes, asking for information about Bolton. They wrote to him and discovered he was Bolton's grandson: he put them in touch with his mother, Maureen Haynes, McKinnon's great-niece, whose DNA matched McKinnon's.

Last week, they were all there at the burial: Maureen Haynes and her cousin, Anne Johnson; Jim Halliday; Fabien Demeusere and even Laurel Clegg, who clutched half a dozen poppies and said she had come to bury 'my boys'.

'I've been working on this case for years and it's really easy to forget it is not just a pile of paper on your desk,' she said. 'These are people who were sons and husbands. All the scientists wanted these men to have a name when they went in the ground.

'Now I work in a coroner's office talking to relatives whose loved ones died last week. What is so surprising and moving is that, talking to these families, there is no difference: their emotions are the same.'

After laying her wreath, Anne Johnson, 73, who used to teach maths in Dorset, said she certainly 'felt a link' with McKinnon, her great-uncle. Her daughter, Andrea, wore a scarf in McKinnon tartan for the burial.

Jim Halliday also laid a wreath. On his way to the service from Canada, he had made a pilgrimage to France Lynch, stopping at the cottage where Halliday was born. 'I felt like he had just died yesterday,' he said after the service. 'I never knew where his body was, nobody did, and all of a sudden you are burying somebody who is your uncle. It is such a wonderful thing to happen.'

On the other side of the low stone wall stood two more men wearing sombre suits. Philip Linnell, 55, and Martin Hemsley, 50, are both great-nephews of Major Henry Linnell, who commanded the 78th Battalion and died at Hallu that day. His remains, too, have never been recovered.

They only met three weeks ago, when Mr Linnell stumbled across information about the reburial on the internet and decided to trace any other ancestors. They drove over from London together, after stopping off at the house in Hackney where Major Linnell was born.

The Canadian authorities think it unlikely, but both like to think their forebear could be one of the three unidentified soldiers reburied here.

In any case, Mr Hemsley said they could not miss the reburial of eight men who had served him. 'They must have been as close as anything,' he said. 'How could we not come and pay our respects?'

There was time for one final surprise. As the descendants shared stories about their ancestors at a reception in the village hall, Ms Clegg suddenly asked for silence and called Jim Halliday to her side.

Then she handed him his uncle's locket. Inside was his sweetheart's name, written in pencil on a piece of cardboard, and two locks of her hair.

A century ago, Sidney Halliday left his home, eventually losing his life and his name. This weekend, his nephew is flying back to that same farmland, Sidney's name restored and his locket safely in his pocket. 'It is part of the family now,' he said.

Caix British Cemetery, Caix, Somme, France

Angus Martin

An Irish friend, Joe Teasdale, sent me a cutting from The Sunday Telegraph of 17 May 2015, pointing out that a Campbeltown-born fatality of the Great War, Lachlan MacKinnon, was mentioned in it; but even without the local element, it is a remarkable story. I contacted the writer, Tom Rowley, to ask if I could use his article in the Kintyre Magazine, and he at once agreed, providing the newspaper itself cleared the request. A day later, I had an e-mail from Ruth Marsh, account manager in the content licensing and syndication department, granting approval. I extend my gratitude to both Mr Rowley and Ms Marsh.

To find out more about MacKinnon and his background, I first checked the Campbeltown Courier microfilm records in Campbeltown Library. I was prepared for the possibility that the circumstances of his death, on 11 August 1918, might have delayed its announcement by months, but on 7 September the Courier reported him killed in action, noting that 'beyond the War Office announcement there are no particulars as to how Private Mackinnon fell'.

Some biographical details followed. His last job before he emigrated to Canada had been with James Girvan, butcher: 'He was a most capable and reliable employee, and being a young man of genial and affable temperament was well liked and esteemed by all who knew him.' He 'joined the colours' in August 1915, arrived in England at the beginning of May 1916, and 'went to the front' in August. After a period back in England, recuperating from a knee wound, he returned to France towards the end of 1917. At the time of his death, his young wife, Christina Rankin from Ballachullish, was living in Glasgow.

In Tom Rowley's account, MacKinnon's name is said to have been added to the 'gravestone in Campbeltown' of a niece 'Morag' who 'died young'. This information, which probably derived from family tradition, isn't quite correct. His name appears on a headstone, situated against the south wall in division 2 of Kilkerran, erected to his parents, Lachlan MacKinnon, born April 1841, died June 1905, and Marion MacEachran, born August 1841, died March 1924. Lachlan's inscription follows: '78th Bn. Canadians, born Nov. 1887, killed in action at Hallu, France, August 1918.' Lachlan's brother Malcolm (1885-1941) appears below him, and below Malcolm there is a final inscription to Mary Marion Wallace, grand-daughter of Lachlan and Marion MacKinnon, born 23 December 1921, died 2 October 1950, and 'cremated at Edinburgh'.

She must be the niece Morag who 'died young', though she was almost 29 at the time. Gaelic Morag was generally Anglicised as 'Sarah' in Kintyre, but 'Marion' - Mary's middle name - was also used for Morag. Lachlan's year of birth on the stone is '1887', and in the following article it is '1888'. His parents' years of birth, as recorded on the stone, are suspect. It is certainly clear from other sources that Marion MacEachran was born around 1850, not in 1841.

Private MacKinnon's parents both bore surnames which are readily identifiable with Kintyre, but when I checked the 1901 Campbeltown Census I discovered that neither was native to the area. Lachlan Snr., a shoemaker, was born in Mull, and Marion, his wife, was an Islay MacEachran. Their two oldest children, John (17), an apprentice draper, and Malcolm (15), an apprentice painter, were both born in Cardross, Dunbartonshire. Lachlan, who was 13 years old in 1901, and a 'scholar', was the first of their three subsequent children to be born in Campbeltown, which must date their settlement here to around 1886. He had two younger sisters, Janet (II) and Isabella (4). Therefore, despite the superficial evidence of these two surnames, MacKinnon and MacEachran, the genealogical trail leads out of Kintyre to the islands of Mull and Islay. (For anyone interested in a somewhat expanded genealogy of these families, Florence McEwan, in Campbeltown Library, and her husband, David, undertook a thorough investigation.)

In 1901, the MacKinnon family was living in the Kirk Close, so named because it led from Longrow to Longrow Church. The buildings, including Hugh Clark's tea-room, which formed the 'close', or entry, were demolished in the late 1950s to create a wider entrance, presumably for the convenience of motor vehicles. Lachlan's widowed mother's address at the time of his death, 39 Longrow Street, represents the same location; the present numbering of the properties on that side of Longrow goes from 35 to 41.

Gravestone in Campbeltownby Elizabeth McTaggart

Another Summer in Kintyre, Angus Martin, The

Grimsay Press, 2015, £12.95.

Yet again, Angus Martin has produced an addictive set of

tales for those of us who live in Kintyre and those who

have left but still carry the place in their hearts. As

in his previous book, A Summer in Kintyre, Angus

hangs these accounts loosely on the peg of his diary of

the year. This book chooses interesting and significant

observations from 2014, but these are used as a

springboard, or time machine, to take him and his readers

to connections with people, places and events in years

gone by. As always, Angus is meticulous in checking his

memory of events and conversations against written

records, correspondence, and his previous diaries.

At one point in the book, Angus comments on the number of deaths and other sad circumstances he is recording. This doesn't need an excuse in an account of social history and people long gone, but the book is not without its humour and some of these anecdotes concern the hazards of cycling, suffered by Angus and others of his acquaintance. I was particularly intrigued by the tale of a 'worthy' who fancied himself as a cowboy: 'He'd answer a knock on the door by cycling down the hallway with his "six-shooters" at his waist.'

Place-names and their derivation continue to be explored in this publication. This will be no surprise to those who have appreciated Kintyre Places and Place-Names, a previous publication.

Much of Angus's valuable notes relate to the flora and fauna of the peninsula of Kintyre. He is in touch with most of the people for whom observing and recording wild life species, numbers and habitats is more than a hobby, and he constantly seeks out their advice and expertise when he needs information and confirmation for his own records. Butterflies and moths dance through some of the pages and we share with him the joy when he spots a small copper or a tortoise shell butterfly, or when the latter spend the winter attached to the ceiling of the building in which he lives.

The reference section and index are as inclusive and exhaustive as we have come to expect from a researcher of such experience. Some of the photographs lack the clarity and sharpness of modem reproduction, but the written text more than compensates for this small irritation. A welcome addition is the inclusion of map references for the places mentioned in the chapters. With an O.S. Landranger or Explorer map of Kintyre, readers can locate these places described in the book and perhaps set out on their own voyages of discovery.

As the book progresses, the reader becomes aware of how much Angus values the memories and views of others. Fishermen and 'wilk' -gatherers, walkers and cyclists, shepherds and farmers, all appear in this travelling tale and all add their own weft to the warp that Angus has established. By the end of the book, the reader will have become a part of the intriguing tapestry that is this land of Kintyre.

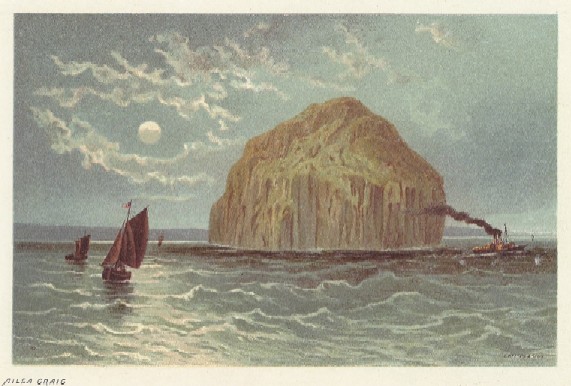

by Murdo MacDonald

The quotation in the title is from the poet William Wordsworth who in 1833 witnessed a solar eclipse from a steamship close to Ailsa Craig. The poet was inspired by the great rock 'in lone sublimity/ Towering above the sea and little ships'. The word 'sublime' is nearly always present in nineteenth century accounts of the island.

Old Print of Alisa Craig

'A mighty volcanic plug rising majestically from the Firth of Clyde', in the words of Rob Close and Anne Riches in the Ayrshire and Arran volume of The Buildings of Scotland series, Ailsa Craig is almost like a hub seen from Antrim, Ayrshire, Arran and Kintyre. Perhaps the view of the rock induces a certain possessiveness among those who see it daily on the horizon. Elizabeth Marrison has remarked on how, as a wee girl on the family farm of Kilmashenachan, Southend, she was always indignant at hearing Ailsa Craig described as off the Ayrshire coast. 'No, it isn't - it's off Kintyre!' Maybe they are like that in Southend. Certainly, Rae (MacLaren) MacGregor remembers that when her teacher once asked her class, 'Where is Ailsa Craig?', the bold Rae piped up, 'Please Miss, it's outside my Granny's window,' as indeed it is - from Feochaig Farm on the Learside of Kintyre.

Group on Alisa Craig

Be that as it may, the island was briefly taken possession of by a small party of Kintyre Antiquarian and Natural History Society members on 5 July 2015, conveyed there by a Kintyre Express RIB. The approach from the west, from Campbeltown, is spectacular, the soaring cliff face white with seabirds in perpetual movement. The group was treated to a complete circumnavigation of the rock, a chance to take in views of the steep heather- and bracken-covered slopes, the gaunt eerily silent North and South foghorns, the Lighthouse and the other buildings which occupy the flat triangle of ground on the eastern side.

It is one of those places that leave the visitor thinking, 'I wish I knew more about geology/botany/ornithology' (in none of which sciences is the present writer competent!) Some features, however, did catch the eye, such as the somewhat surprising appearance of the creamy white flowers of numerous Elder trees clinging to the cliffs, unexpected in this harsh, otherwise treeless environment. The Tree Mallow (Malva arborea), reported as growing wild here, is a plant more associated with the cliffs of East Lothian, but on the date of the visit the only specimens noted were in the confines of a former garden. Feral goats are mentioned in nineteenth century accounts, but there was no evidence of these animals. Ailsa Craig rabbits were once culled in huge numbers and they are still abundant on the higher slopes of the island, according to the intrepid George McSporran, who successfully climbed to the summit (1109 feet above sea level) with his son Sandy and Lee Holland.

But it is the seabird colony which gives the island its status as a major nature reserve of international importance. The gannet colony - once a human food resource - contains tens of thousands of breeding pairs and is the third largest in Scotland, after St Kilda and the Bass Rock. As mentioned before, it is the great gannet-laden cliffs that greet the traveller approaching from the west. In the nineteenth century, it was customary for passing steamers to alarm the birds by firing a gun, the whirling clouds of the startled creatures presenting a scene that was considered 'wondrously sublime'.

By 1884, the firing of guns had been prohibited, according to a report in the Argyllshire Herald (31 May) of an excursion to Ailsa Craig from Campbeltown on the S.S. Kintyre. Instead, 'the steamer's fog horn was sounded with the view of rousing the vast congregation of sea-birds ... and the sight of the birds circling in the air was not soon forgotten'.

From 1404 until the Reformation, the island belonged to the Cluniac abbey of Crossraguel, near Maybole. Ailsa Craig Castle dates from this period, but little is known about its origin or purpose. It stands high on a steep slope, which deterred the less agile of the Kintyre party from exploring it. What purpose could a building like this possibly have served?

The Lighthouse was constructed in 1883-86, 'a surprisingly late date to light such a major and unforgiving obstacle', to quote Close and Riches once more. It was built to the design of the famous lighthouse engineers, D. and T. Stevenson. The gleaming white tower, II meters high, fronts a complex of derelict ancillary buildings.

The lighthouse was automated by the Northern Lighthouse Board in 1990 and its keepers withdrawn. To members of the KANHS group, used to visiting the ruins of settlements long abandoned, there was something discomfiting about these lighthouse buildings, still roofed, still retaining bits of furniture, doors wide open.

Contemporaneous with the Lighthouse are the two massive fog signals on the north and south sides of the island. Roughly cone-shaped and constructed of thick concrete, these signals were originally powered by gas engines and could be heard up to fifteen miles away. Oil replaced the gas in 1911 until the signals were discontinued in 1966 and replaced by a new system, itself discontinued in 1987. The skeletal remains of the gasworks lie open to the winds. A tramway, cable-hauled, leads from the landing-stage to both the gasworks and the lighthouse buildings.

And finally - the famous Ailsa Craig granite and curling stones. The island quarries operated from the 1880s until 1971. The stones were roughly hewn on the island before being shipped to Mauchline for finishing. Signs of this industry are to be found in piles of shaped stones lying where the stoneworkers' sheds once stood. Needless to say, these lumps of granite provide instant souvenirs, and, sure enough, some were carried in triumph back to Campbeltown.

Copyright belongs to the authors unless otherwise stated.

It organises monthly lectures in Campbeltown - from October to April, annually - and has published its journal, 'The Kintyre Magazine', twice a year since 1977, in addition to a range of books on diverse subjects relating to Kintyre.

CLICK HERE for Correspondence and Subscription Information.