THE KINTYRE

ANTIQUARIAN and

NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY

MAGAZINE

Issue Number 79 Spring 2016

The Bodach and Cailleach

CONTENTS

- CONTENTS

- Readers' Comments

- The Night Campbeltown Press-Ganged the Press-Gang; Hector MacMillan

- A Sailor's Memoir, 1940-1941: Part 2; Edward Duckworth

- The Rescue Tug Englishman; Ian Wilson

- The Fate of the Noss Head of Carradale; Finlay Oman

- The Story of Andrew McKellar; Ronnie Roberts

- Alexander Thorn and Neil Bone; Ronnie Roberts

- A Canadian in Campbeltown; Carol McNeill

- By Hill and Shore; Angus Martin

- Ailsa Craig and Gigha Revisited; Angus Martin

- The Cailleach and the Bodach; Frances Hood

- Glens of Antrim Historical Society; R.G.T. Nelson

by Ronnie Roberts

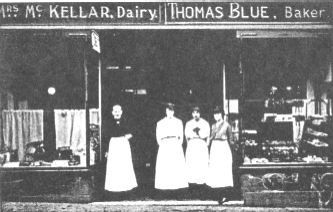

For more than a century, Mrs McKellar's Dairy was an iconic shop front next door to Blue the Baker in Main Street, Campbeltown. It was founded by Mrs Janet Hamilton McKellar in 1866 and subsequently run by her daughter Maggie (Black) and then her two grand-daughters, Margaret and Jenny. It was always known for the quality and safety of its milk, supplied to customers in their own jugs or in tin milk-cans which delivery boys suspended from the handlebars of their bicycles.

Janet Hamilton was a member of the family of Andrew and Barbara Hamilton (nee Sym) who came to Kintyre from Carluke, Lanarkshire, in 1855. Originally they came as farm workers to Killeonan estate, but in 1870 moved to The Flush, where Andrew was granted a tenancy.

Janet was Andrew and Barbara's youngest daughter (born in Carluke in 1846) and was working as a dairymaid in Breachacha, Island of Coll, when she married a Campbeltown man, David McKellar - variously described as a farm labourer, shepherd and fisherman - on Coll in 1865.

They returned to Campbeltown, where Janet set up her eponymous 'Mrs McKellar's Dairy' in Main Street, which always traded under her name or, later, that of her daughter Margaret (Maggie Black). Her husband David McKellar was also from the Killeonan area (his place of residence on his marriage certificate was given as Dalrioch). Latterly he became a carter, mainly transporting peats from the Laggan to the distilleries in Campbeltown, or goods to the harbour. Unfortunately, he broke his hip falling into a ship's hold and never worked again. Janet's business therefore was the family mainstay while she brought up her six children.

Mrs McKellar's Dairy at 46 Main Street, Campbeltown. Janet is on the left.

Descendants of these six children have made their mark internationally in various fields, including the arts, economics, diplomacy, chemistry, fisheries and nutrition. None, however, has had as much influence as the offspring of their youngest son, John Hamilton McKellar.

John was apprenticed as a carpenter and joiner and lived in the family home above the dairy in Main Street. He entered the Campbeltown branch of the Associated Carpenters and Joiners of Scotland on June 5, 1897. Work was apparently scarce in Kintyre, and in 1903 he went to South Africa to join his oldest brother William. There he worked first for contractors in Malvern, a suburb of Durban. He did not enjoy life there, though he did manage to amass a large collection of very colourful butterflies, and returned to Scotland in 1905, bringing his collection with him.

Finding no work there again, he set out for Canada on July 29, 1905, on the Allan Line's ship, SS Sicilian, from Glasgow to Montreal. His original plan was to travel on to Yonkers, New York, where he was to work for a cousin, but on the boat he made friends with other Scots who were migrating to Winnipeg and he decided to go along with them. He spent one winter there, but finding it unacceptably cold, he moved again, this time to Vancouver, BC. There he found work and settled happily into the Scottish community that was growing quickly on the west coast.

1908 Wedding of John and Mary - Andrew McKellar 1938

In 1908 he returned to Campbeltown to visit his family. During his visit, he was taken by a friend to shoot at Arnicle in Barr Glen. By chance, while he was there, he met Mary Littleson, who lives at Killegruer, where Mary's parents, Neil Littleson and Jean Smith, farmed. The Littleson family was originally from Gigha and the name is an Anglicisation of the Gaelic McFiggan (= son of the little one). They were members of the Free Church and spoke Gaelic, and Mary attended a Gaelic church in Vancouver after she settled there.

Mary and John were married on 23 March 1909 and left for Vancouver later that year. Andrew, the first of their six children, was born almost immediately they arrived in Canada. As with many emigrants, however, there was a hankering for home, and the family travelled back to Campbeltown in 1914. This visit convinced them that their future did indeed lie in Canada and they returned to Vancouver shortly before war broke out. Apparently Mary now felt that Canada was her home, and she had no wish to visit Scotland again. Certainly this was the last time either of them would go back to their homeland.

Although all of the McKellar children did well, their influence and indeed that of their cousins, the diaspora of the Hamiltons, the McKellars, the Littlesons and the Smiths being quite remarkable in many areas, the most distinguished was their first-born son Andrew (1910-1960), the subject of this article.

After returning to Vancouver from Kintyre with his family in 1914, at the age of four, Andrew McKellar was schooled there until entering the University of British Columbia (UBC) at the very early age of 16. He graduated with first-class honours in Mathematics and Physics and from there he went to the University of California, Berkeley. An MS and PhD in Astrophysics were followed by a fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

His post-doctoral fellowship expired in 1935, just before the eminent director of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, John S. Plaskett, was due to retire. (By a coincidence, unknown to either of them, Plaskett was the nephew of Campbeltown-born Dr Duncan McEachran; see Kintyre Magazine 73.) McKellar was appointed to work there and began studies on the orbits of binary stars, an area favoured by Plaskett. However, he soon developed his own programme in the field of molecular spectroscopy and almost immediately commenced his remarkable sequence of discoveries.

In 1940 he became the first person to detect the presence of matter in interstellar space when he identified the spectral bands for the organic compounds cyanogen ('CN') and methane ('CH').

One year later, in 1941, he determined the temperature of the cyanogen molecules and deduced that the interstellar environment in which they are found is very cold, approximately -271°C. It was the first direct measurement of the temperature of the universe, and modern measurements with much more sophisticated equipment have confirmed this first finding. It was also the first theoretical definition of the cosmic microwave background which has driven so much of our understanding of the 'Big Bang' and 'black holes' which are implicit in modem theories of the birth of the universe.

Sir Fred Hoyle, the eminent British astronomer, has pointed out that, in his view, McKellar's keynote findings were of epochal significance. He believed that they received less attention than they should have, only because they were published in 1941 and the world was at war. When eventually it became possible to start thinking about basic astrophysics again, McKellar's work was overlooked by the new generation. This was not helped by the fact that his work was particularly relevant to astrophysicists but was published in general astronomical journals, which those really interested in astrophysics would be less likely to access.

Shortly after these discoveries, McKellar was drafted into the Navy, where he worked on classified research, attaining the rank of Lieutenant-Commander. He never referred to these key pre-war findings after he returned from war service, his interest moving to the study of the different molecules in stars and comets.

In 1964, however, two American astronomers, Penzias and Wilson, in a classic example of serendipity, directly detected the cosmic microwaves which McKellar had so accurately predicted and defined theoretically twenty years before. They did this quite by accident, believing them, initially, to be interference on their aerial from pigeon faeces.

In 1978 Penzias and Wilson were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. Unfortunately McKellar had died of chronic lymphosarcoma in 1960. Although disputed, Canadian scientists believe McKellar would have, and certainly should have, been the 'third man' on that prize, but it cannot be awarded posthumously.

Dr. McKellar (R), in front of mirror at Dominion Astrophysical Observatory

Andrew McKellar was a remarkable scientist. He was also a remarkable man. Although his life was blighted by his chronic cancer, which he fought for 15 years, he was, according to his daughter, ' ... loved by everyone he met, and even my mother couldn't really think of a bad thing to say about him, ever, except perhaps that he always was off to the bathroom at the exact time that she wanted to put dinner on the table, and he liked to sort of cut things pretty fine when getting to airports, ferries, etc. We call it "McKellar timing". As far as I know, though, the only time he was late for something was when he was trying to catch a ferry somewhere and arrived when the ferry was leaving the dock!'

He was also considered by his colleagues to have strong views on matters of justice and fairness, especially in scientific attribution of credit and he was very strongly against sex discrimination at a time when it was generally the rule.

Although he was possibly not internationally acclaimed as much as he deserved, Andrew McKellar was celebrated by his peers in that they named a new 112 cm telescope, The McKellar Telescope, after him. A crater on the moon, the McKellar Crater, and a minor planet, McKellar 1929TDI, also celebrate his distinctive contribution to our knowledge of the universe.

Professor Roberts extends his thanks for photographs to Professor Barbara Fleming, Professor Ronald Hardy and Mr Ian McKellar.

by Frances Hood

If you drive up Glen Lyon and leave your car at the dam, then start walking until you come to Glen Cailleach, you will be in for a pleasant surprise. Situated at the side of the Cailleach burn is a small stone house. On 1 May, the inhabitants of this house would be released in order to bring prosperity and fertility to the area, and a bannock would be broken. This Pagan custom was practised up until recent times by the local people who drove their cattle into the hills for the summer, then took them back down in the autumn. The stone family would also be put back in their house and sealed up for the winter.

The inhabitants of the house consist of the Cailleach (Gaelic: 'Old Woman'), the Bodach ('Old Man') and some children. The Glen Lyon family had five members, all made of stone and mostly bell-shaped. It is reputed that the Cailleach gives birth every hundred years. It is more than ten years since I visited the site and heard that the old shepherd who looked after the house had died. It was already June and I found the house still sealed up. My friend and I decided to open it and bring the family out, but when I got home I felt guilty and wrote to a well-known historian. He said we had done the right thing, but he was worried about what might happen in the future.

On the island of Gigha there is also a pair of stones called the Cailleach and the Bodach, and I was amazed to hear that certain locals know where three of their children are. The two stones have no house, but sit on top of a small hill in a field. Some of the islanders are anxious to protect the site, so I contacted Historic Scotland to have it made a scheduled monument. Unfortunately, that body was not interested, but the stones are very important to the locals. If one of the stones should fall over, it is immediately put back up again. Stories of goblins are connected with these stones, as they were reputed to walk about the country and be seen by locals. As these stones and their stories could be more than two thousand years old, it is sad to think that soon their memory will be lost forever.

An account of these stones may be found in Anderson's The Antiquities of Gigha, revised and reissued in 1978, from which edition the following is extracted (p 133): 'These names may enshrine a memory of that bodach "who walked the heath at midnight and at noon ", and of the cailleach, the night-hag. It is said that the Irish fishermen, who used to frequent the Gigha harbours, visited the hill, and, if they found the stones prone, placed them upright again; and if separated, put them together. The islanders thought the stones had some religious significance for the Irish, but they themselves treat the stones very much in the same way today ... '

Copyright belongs to the authors unless otherwise stated.

It organises monthly lectures in Campbeltown - from October to April, annually - and has published its journal, 'The Kintyre Magazine', twice a year since 1977, in addition to a range of books on diverse subjects relating to Kintyre.

CLICK HERE for Correspondence and Subscription Information.