CONTENTS

Book Review

Angus Martin

In the Wake of Mercedes Gleitze, by Doloranda Pember, The History Press, 2019, 288 pp., £16.99.

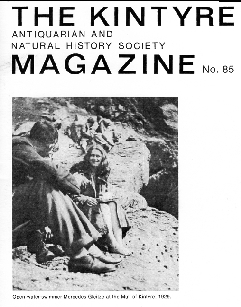

I must admit, at once, to having had a very slight involvement in this book. The author contacted me in 2015 to say that she was writing a biography of her mother, the open-water swimmer, Mercedes Gleitze. I had been aware of Ms Gleitze's courageous attempts to swim the North Channel in 1929, and, when the swim was finally accomplished in 2012, by a South African, Wayne Souttar, I published a brief article in this Magazine, 'North Channel Swim' (no. 72, pp. 18-19). I mentioned, in that piece, a photograph of Ms. Gleitze which I had seen years before and had been unable to trace. In 2012, it turned up, in the possession of the late Mr Duncan Watson, Southend, and I forwarded a copy to Doloranda Pember, who has used it in her book, with two others, taken at Rubha na Lice, near the Mull. Mr Watson's photograph, which appears on the cover of this issue, may also have been taken at Rubha na Lice, or the location may be Sron Uamh, further east, which Ms. Gleitze also used as a starting-point.

In all, Ms. Gleitze made eight attempts, by various routes, to swim the North Channel. Her last, on 16 September 1929, from Rubha na Lice, came tantalisingly close to success, but, having been in the sea for more than 11 hours, she succumbed to exhaustion just a mile and a half from Torr Head on the Antrim coast, and, on medical advice, gave up. Later that month, she returned for yet another attempt before the onset of winter, but, in the event, she spent three months on Sanda as a guest of Alexander Russell, the island's owner, and his hospitable family. As the author remarks: 'It would have been a healing time for her after the endless battles with the unyielding Irish Sea. She spent long hours in the island's caves, planning and organising future ventures, as well as writing the beginnings of her memoirs.'

I have, understandably, concentrated on the Kintyre content of this book, which constitutes but a tiny part of narrative whole, but a part, nonetheless, which will be of great interest to local readers. The book, as a whole, presents the remarkable story of a woman who was, in her time, an international celebrity when such status was less easily earned than nowadays. Ms. Gleitze was of working-class German parentage and was born in 1900 in Brighton, where she learned to swim. She would later declare: 'I know of no sensation but that of calm pleasure at the prospect of another tussle with those "calling" waves. When one loves, one is not afraid.' In 1927, she became the first woman to swim the English Channel, and, during the subsequent six years, undertook a succession of record-setting swims around the world. Her sporting and feminist credentials aside, she possessed a strong social conscience, which motivated her, in 1928, to establish the Mercedes Gleitze Homes for Destitute Men and Women; the royalties of her daughter's book will, appropriately, be donated to the Mercedes Gleitze Relief in Need Charity, administered by Family Action.

On 6 December 2017, in the company of Alison Diamond, Archivist of the Argyll Papers at Inveraray, I was privileged to be given a mini-tour of Southend, birled along by an enthusiastic Elizabeth Marrison on her home turf. I was particularly grateful to Elizabeth for taking us to see the stone cross at Macharioch erected to the memory of George Douglas Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll, by his widow, in 1901, the year after his death.

The memorial stands boldly upon Dun Dubh, a promontory commanding a panoramic vista across the North Channel to the Antrim hills. The cross is mounted upon a plinth bearing carved inscriptions in Gaelic, Latin and English, the whole structure being about 21 feet in height. It is constructed from red sandstone imported from the Comcockle quarry in Dumfriesshire. When new, the freshly cut stone must have stood out, startingly red, against the cool green of its hinterland.

The contractor for the hewing and erection of the monument was Neil MacArthur, mason in Campbeltown, and it could have been no easy task for him and his men to transport and then manhandle the huge blocks of stone into position.

Its inauguration was not propitious. Barely two weeks after its erection, it was cast down, the victim of an exceptionally violent easterly gale on 12 November 1901, which caused widespread havoc and loss of life throughout the British Isles. Once again, Neil MacArthur was called upon, to strengthen and re-erect the monument early in 1902.

The memorial may be of more than local significance. Its design, and presumably also its specifications, were drawn up by a woman, Helen J. D. Campbell of Blythswood. Her name is attached, almost as a footnote, to any account of a much more famous structure, St Conan's Kirk, Lochawe. This is a category A Listed Building, a strange but hugely impressive church, visited annually by thousands of tourists and a popular wedding venue. Its designer is always identified as Walter Campbell, Helen's younger brother and an amateur architect.

But the existence of the Macharioch memorial raises doubts. Has Helen's input into St Conan's Kirk been underplayed? From 1914, following the death of her brother, Helen supervised the building of the church until she died in 1927 at the age of 80 years. Work on the structure ceased in 1930. So, how much of St Conan's Kirk is in fact the realisation of a vision by a talented, but side-lined, woman?

Helen moved in the highest circles of society. She was a close mend of HRH Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria. The princess was a gifted artist and contributed the design of a stained-glass window in St Conan's Kirk. Coincidentally, she spent a fortnight at Macharioch House in 1871, during her 'marriage tour' with the 8th Duke's son, John, Marquis of Lome, who was given the mansion-house by his father as part of his marriage settlement.

What led to Helen's involvement with the Macharioch memorial cross was her friendship with Ina MacNeill, Duchess - later Dowager-Duchess - of Argyll, who had taken up residence in Macharioch House. The Campbeltown Courier of 13 October 1906 records Helen's presence at a 'Grand Concert' held in Southend Public School under the patronage of the Dowager-Duchess, the proceeds of which were in aid of the restoration of Iona Abbey. (Incidentally, the weathered original stone tracery of one of the windows in the Abbey, removed during the restoration, now adorns St Conan's Kirk.) The signatures of the two ladies appear together in the Visitors' Book of Campbeltown Free Library and Museum on 16 September 1909 (see my article in Kintyre Magazine 71).

When erected, the cross was a private symbol of a widow's grief, but times change. It now stands like a pilgrimage way-marker beside the Kintyre Way.

A ceilidh with Hamish Henderson at Smith Drive in 1956

An unusual ceilidh was held recently in the home of Mr William Mitchell, Smith Drive, Campbeltown. The programme was almost entirely of Kintyre folk-songs. And there was 'a man with a mike' there to record the songs. He was Mr Hamish Henderson of the Scottish School of Folk Lore Study. *

One song he particularly wanted to hear was 'The Boys of Callibum' sung by Alex McShannon of Drumlemble. 'The Boys of Callibum' is the story set to music of two local lads who were about to emigrate to America. Before they go, the lads sing the praises of their native countryside and express the sadness they feel in their hearts that they will soon have to leave such beautiful surroundings.

Mr John McShannon of Crosshill Avenue, Campbeltown, sang several of the well-known Kintyre airs, including 'Island of Davaar', and James McShannon, Drumlemble, the eldest of the three brothers, sang 'Glenbreckerie'.

Mr William Mitchell also sang a number of songs which he previously recorded. Other singers were Mr Sandy McNeill of Glenbarr, Mr Malcolm Thomson of Drumlemble, and Mr Robert Hamilton (77) of Trodigal Cottage.

The recordings Mr Henderson made will be filed in the special folk-lore section at Edinburgh University buildings. Campbeltown Courier, 20/12/1956

* School of Scottish Studies, established in 1951.

Link with the Cholera Plague

On Tuesday last, while digging operations were in progress in connection with the drainage of Castleacres, the workmen came upon a coffin, painted black, and containing the bones of an adult. Castleacres was used as a place of burial during the cholera plague which visited Campbeltown in the year 1832, and it is supposed that the coffin and human remains were then interred where they were

found this week.

Argyllshire Herald, 13 February 1904.

There are few more interesting sights about a farm than a sheep-shearing. Though the work is arduous and fatiguing, it is looked forward to with pleasant anticipation by the farmers and their men, for it is usually a jolly event, out of which a great deal of fun is got. One which the writer attended the other day on a hill farm of Kintyre was essentially of this kidney.

The shearing began about six o'clock in the morning, and, according to custom, every 'neebor' [neighbour] farmer sent a shepherd, or a son, or else came himself, to assist. Some of them, too, had walked five or six miles before commencing their day's darg [work].

This particular farm extends to many scores [sic] of acres of rough, hilly country. The previous two days had been devoted to an in-gathering of the scattered flocks, and now, on the morning of the shear, the sheep, to the number of about 1000, are collected in a natural 'bucht' - a deep hollow near the foot of a hill, encircled by a light portable paling [fence] with a small pocket at one end. This pocket, or smaller enclosure, is connected with the larger by a slap [gap], through which the sheep are admitted one at a time. Once in there, they are easily caught, and are then dragged off to the shearing stools.

These are situated near at hand - some eight or nine of them - and are about three feet high, with hollowed-out tops. It is a peculiar thing about a sheep that, when placed upon its back upon a concave surface, it is as powerless to move as a turtle which has been turned over on its shell. But the sheep can still kick, though it cannot rise; and some shearers tie their legs together before commencing operations upon them. Others, more expert, discard the use of the rope.

What surprises the novice is the small number of shear-cuts required to cut off a fleece. The clipping begins at the under part of the body. Snip, snip, snip and a broad strip of the pure white wool below is exposed to view; snip, snip, snip - and the fleece comes away from the whole side and hangs over like a flap. Then the other side is treated in the same manner, and in three minutes or so the poor animal lies there denuded of its garment, its big eyes showing a look of pained surprise that it should be thus unceremoniously dealt with.

The scene during all this time is one of cheerful animation. The air is laden with the baa-ing of the ewes and the lambs; the shearers laugh and joke at their work; and the collies show an appreciation of the importance of the event by scampering about in a state of alert excitement.

As the ewes are released from the shearing stools, they begin in a most woeful way to cry their lambs to foot; while the lambs, unable to recognise their mothers in their summer dresses, add their discordant voices to the general babel. Meanwhile the shearers are treated to whisky galore. The jar and the horn cup circulate with a freedom which must be fatal to the sobriety of any but Highland farm folk, and the whisky is all drunk raw.

The rapid circulation of the cup puts one in mind of the Highland minister who thus warned his flock against the evils of intemperance. 'My friends,' he said, 'there will be no harm at all, at all, in a dram. You may take a dram when you will rise up in the morning, and give the wife a dram, and you can have a dram when you go up the hill, and maybe when you come down the hill; and there is no harm in a dram after dinner; nor will you be wrong to take a dram when you have got your supper; and nobody can say it is an ill thing to take a dram or two or three before you go to bed; but, my brethren, you should not be aye dram-dram-dramming.'

It is little effect, however, that the usque-bagh takes on the hard-headed shearers. In fact, it would seem to increase their working capacities, for, as they warm to their labours, the keenest rivalry begins to be shown as to who shall shear the greatest number of sheep, and this leads to endless chaffing and exchange of ironical compliments. Swatches of Gaelic are thrown from tongue to tongue, and odd verses of song lend variety to the flow of talk.

As these tall, lusty hillmen, stripped to the shirt, handle the heavy sheep with as little apparent effort as though they were kittens, one cannot help thinking of Big Jan Ridd's exploit when his sheep were buried in the snow, and he carried the whole lot home, two at a time.

Hundreds have been clipped before mid-day comes, with its welcome respite of half-an-hour for dinner, and another dram, and a draw at the pipe. Then the work is taken up again with renewed energy and vigour. Gradually, as the afternoon wears late, the number of unshorn sheep in the buchts becomes beautifully less, and, tired and weary as the shearers are, they finish up with a spurt, and celebrate the clipping of the last sheep by having recourse to the jar, as usual. The sheep, it should be mentioned, are all marked or branded after being clipped, and are then allowed to wander away at their own sweet wills. As for the wool, it is packed into big bags and sent to that be-all and end-all of Kintyre existence - 'ta poat'.

When the shearing is finished, there is an adjournment made to the farmhouse, where the jaded shearers are refreshed with a welcome douch at the pump, followed by a rousing tea. The evening generally closes with a game at cards ha'penny nap the favourite - and there is here again no lack of the wine of the country. Sheep-shearing is about the only part of farm work to which the old custom of neighbour farmers helping one another still applies. Perhaps this is the reason of its popularity. At any rate, the shearers, as they sat round the table that night, were unanimous in expressing the hope that mechanical appliances might never come to do away with the hand-shearing of sheep.

Argyllshire Herald 5 October 1901, from the Glasgow Evening News.

FIRST FEMALE CYCLIST IN CAMPBELTOWN. 'The first lady bicyclist was seen in Campbeltown on Saturday afternoon. The fair rider seemed a novice at the work of bicycle riding.' Argyllshire Herald, 9 September 1893

I spent five years as Curator at Campbeltown Museum - it was there I met Frank Chinn. Frank was a teacher with the Learning Support Unit at Campbeltown Grammar School. We met in August 2016 to discuss a forthcoming project his class would be doing with the Museum. Julia Hamilton from the Kilmartin Museum Education Team, Frank Chinn and I sat together at the long wooden tables just inside the marriage room at the Burnet Building, dreaming up plans.

Frank was full of inspiration and knowledge. He knew the local landscape, much better than I, living and working as he did at Dalmore Farm off the Southend road. Frank suggested the students explore Glenrea township, above Glen Breackerie. He interacted with his students with ease, kindness and humour. He wanted his students to know the place - its plants, the incline of its slopes - and to investigate the stone remains that were once walls of houses and byres; to listen for the call of the birds; to learn the names of the families who had spent generation upon generation there, and who were now gone.

The summer after this project was complete, Frank visited me in the Museum.

He wanted to study for a Ph.D. He told me his undergraduate work had been in archaeology and that he aspired to work in museums. Months later we met again and I learned that his plans for the Ph.D had not come to fruition. I could tell he was disappointed. He asked if he could volunteer in the museum. I told him that as he was serious about a career in museums, I would like him to become an intern. I also told him I did not believe internships should be unpaid. I secured a budget and Frank joined me as Intern in Museum Practice on 28 February 2017. Initially for one hour a week, then, when Frank enrolled with Ulster University to gain his formal museum studies qualification via part time remote learning, Frank and I spent every Tuesday together. He began his one day a week on 24 October 2017. I knew by this time that I would be leaving my post as Curator, and was actively training Frank to take up the mantle. On 6 February 2018, Frank and I spent our last working day together, as I left my post to give myself fully to caring for my parents in Helensburgh.

Today I write this tribute to Frank. It is the 28th day of February 2019. I spent the last three days in Kintyre, at Dalmore Farm. My partner Steve and I have been graced with Helen Chinn's loving hospitality as I sorted through Frank's books on archaeology, history and museum studies, with the aim of helping each book find a good home. As I surveyed the titles, I asked Helen, 'Did he read them all?' I realised that Frank's depth of knowledge was profound. He did not ramble at length using a lexicon or concepts far beyond the ken of the listener. He communicated simply, with that distinctive Solihull accent I loved.

The new Curator at Campbeltown Museum, Meghann Logue, took up her post last week. By happenstance, we were able to bring Meghann down the road to Southend, to visit Dalmore. Meghann studied archaeology and history, then

completed her museum studies qualification in November of last year. I wondered if she might find some of Frank's books useful. She was able to select many books with which she hopes to create a reading comer in the Museum. This had been one of Frank's dreams. One of mine had been to create a museum apprenticeship programme.

I write now trom my diary of yesterday:

'So many encounters, moments, conversations to record of the past few days spent with Helen and Benny the Dog at Dalmore Farm. Not least the Red Admiral, wings closed, hibernating in the furthest, lowest comer of the sitting room where I was working at cataloguing then boxing Frank's books before we eventually moved them all out, dismantled the shelves and carried the bookcases themselves out to storage. The farm is to be sold. The house cleared. At the final whistle, the Red Admiral. Helen cupped it in her hands and tried several places in the small sitting room, before eventually cupping it once more and releasing it at the threshold of the conservatory door to the outside. The butterfly chose to flyaway into the sunshine of the day.'

I hope many of you will share your inspiration and knowledge, your love of this place that has always been, or that you have made your home, round the table in the marriage room of the Burnet Building, as our shared dreams continue to unfold and take flight.

I thank Elaine McChesney for her tribute, written at very short notice, to her friend and colleague, Frank Chinn, who died, aged 43, on 18 September 2018. Frank had a deep interest in Norse history, and in January 2015 delivered a well-received lecture to our Society on 'The Norse in Kintyre', which was sandwiched between articles he wrote for this Magazine on 'Norse Place- Names in Kintyre' (part 1 in no. 76 and part 2 in no. 77).

Editor

Editorial Miscellany

A CAVE NEAR BORGADALE. This spring, I hope to visit and write about a cave in a cliff face between Borgadale - east of the Mull of Kintyre - and Glemanuill Port ('Port Mean' on O.S. maps). Among other interesting features, there is a stone wind-break at its entrance, indicating past human occupation. The cave is not easily reached and enquiries so far suggest that few people know of its existence. If any reader has information on it, please contact me.

NEGLECTED GRAVE MONUMENTS. There appears to be some progress being made in this vexed issue. Representatives of our Society met with Oliver Lewis of Historic Environment Scotland on 30 January to discuss the condition and exposure of the several fragmented late medieval monuments in Kilkerran, while a body of volunteers, Friends of Kilkivan Cemetery, is being formed with the object of maintaining that graveyard and protecting its legacy of carved stones, which were covered by rubble (since cleared) when part of the chapel wall collapsed in 2010. It is a disgrace that these magnificent products of native art suffer official neglect, while millions of pounds of public money can be handed to some aristocrat to stop a grossly over-valued painting being sold out of this country, in which it was never culturally relevant, except in a secret niche of privilege: a 'loss to the nation' - what nation?

WILLIAM GREENLEES, 'ARTIST'. I intend to publish, in the next issue of the Magazine, an account of a visit to the Argyll Settlement, Illinois, by William Greenlees, who was a relative of John Greenlees, founder of the Settlement in 1836. William, who died in 1879, was born in Campbeltown and was described as an 'artist', but I have so far failed to trace any surviving work positively attributable to him. Can any reader supply infonnation on his career?

CUTHBERT SPENCER was an English gardener and photographer. His postcards of picturesque scenes, villages and steamers in Cowal and southern Argyll, in the earlier part of the 20th century, are still traded on the internet. He came to Kintyre prior to 1900, for on 24 October of that year he married Annie McKinlay in Skipness and in the 190 I Census they were living in Clachan. She died later that year and by 1911 he was in Tighnabruaich. His life is being researched by Geoff Newton, who would welcome any infonnation on his time in Kintyre. Please contact geoff.newton@tiscali.co.uk or 01700811556.

A DOCTOR IN CAMPBELTOWN BETWEEN THE WARS. I have Lady Mary Davidson (née Mactaggart) to thank for sending me a chapter from a book published in 1999, Pipe Lines, by Dr James Richard. He came to Campbeltown in the late 1920s to share, albeit briefly, the medical practice of Dr James Pearson Brown, who was Mary's great uncle. Much of the chapter concerns the author's working relationship with Dr Brown, for whom he had great respect, but there are passages of more general interest and I shall quote three of these.

'It was in Kintyre that I developed my affection and respect for the yeoman of Scotland - the ordinary countryman, be he farmworker or roadworker. The city man's idea of a half-witted type with no imagination and no finer feelings was replaced by a wondering respect. Over the years this increased until I still count many ploughmen and dairymen among my friends. They do not take you into their confidence easily, being naturally shy and suspicious of strangers, but when you do become their friend, one cannot ask for better. I have always thought that the finest types of men you can ever meet are shepherds, gamekeepers and lighthouse men. These lonely people have matured beyond most of us and have an equanimity seldom met in the more harried urban dweller. They are usually highly literate with a broad appreciation of the classics and nearly all have a hobby connected with the study of nature - keen botanists and expert ornithologists, for instance - but it is their calm outlook and apparently inborn judgement of their fellows which I have always admired.'

'My training in midwifery was acquired in the wee houses of Kintyre. There was no consultant obstetrician available and a GP had to do the best he could ... It was a rough and ready training and many times I had to sweat over some malpresentation or any other complication alone in the hills with only a granny or neighbour woman to help. It certainly taught me self-reliance and to make do with what was at hand, which frequently was very little. I still shiver when I think of what we had to do unaided - cases which would now be safely ensconced in a maternity unit. My very first transverse lie was in a shepherd's house away up in a glen above Peninver on the east coast of Kintyre. Luckily it worked out all right, but luck was needed.'

'Clearing out a placental fragment four days after a confinement at a shieling in Gigha still appears to me the most daring thing I ever did, but again my luck held. That Gigha trip was one of the peak experiences of my life. Our practice was covering for Dr Malloch, who had one of the old Highland and Island subsidised practices at Muasdale on the west coast. I had been about six weeks in Campbeltown when one night we got a call from Malloch's housekeeper. Dr Brown turned to me and said this one was for me, as that was what he had an assistant for. I jumped at the idea and next morning I sallied forth armed with a bag full of assorted cutlery and a bottle of chloroform, plenty of iodine and some quinine solution.

'On arrival at Muasdale, the housekeeper told me a motor boat was waiting for me at Tayinloan to take me across to Gigha. Thank Heaven it was a calm day, one of those perfect winter days, the ground white with hoar frost, the sky bright blue and very little wind. I sat like a duke in the stern of the ferry, gazing at the purple outlines of Jura and Islay on the horizon and puffed my pipe. This was what doctoring was about, I thought, and wasn't life wonderful.

'On arrival at the pier most of the populace of that little island was there to see the doctor arrive. And there I was, the sole representative of medical science within thirty to forty miles. I was assisted into a pony and trap and we drove off in triumph northwards. A mile or two up the road, the driver stopped and pointed to a path going up the hill to the west coast. Whereupon I set off to trudge up and over the small island to reach the shieling near the far shore where my patient lay. '

Copyright belongs to the authors unless

otherwise stated.

The Kintyre Antiquarian & Natural History Society

was founded in 1921 and exists to promote the history,

archaeology and natural history of the peninsula.

It organises monthly lectures in Campbeltown - from

October to April, annually - and has published its

journal, 'The Kintyre Magazine', twice a year

since 1977, in addition to a range of books on diverse

subjects relating to Kintyre.

CLICK HERE

for Correspondence and Subscription Information.

The Society website is at http://www.kintyreantiquarians.uk

358